The modern factory floor is no longer just a collection of mechanical gears and high voltage wiring. It is a massive, pulsing web of data. Every time a proximity sensor trips, a Variable Frequency Drive (VFD) ramps up, or an operator touches an HMI screen, a series of digital messages are flying across the plant floor. In this environment, IP addresses act as the critical digital coordinates that ensure these messages reach the right destination. Without a rock-solid understanding of how these addresses are structured, you aren't just an engineer or a technician; you are effectively flying blind. In the world of Operational Technology (OT), an incorrectly assigned IP address isn't just a software error. It is a stalled production line, a safety hazard, or a troubleshooting nightmare that can cost a facility thousands of dollars per minute in downtime.

It is easy to get caught up in the excitement of opening software like RSLogix, Studio 5000, or TIA Portal to start configuring a new system. However, jumping straight into the software without mastering the underlying networking theory is a recipe for disaster. We have all seen the technician who spends hours clicking through menus only to realize that their laptop simply cannot "see" the PLC because of a basic subnet mismatch. This is why we focus so heavily on the "why" before we ever touch the hardware. Understanding the logic behind IP assignments allows you to build a mental map of your system. This foundation ensures that when you finally do enter the lab or step out onto the plant floor, your configuration is intentional rather than a result of trial and error. Mastering the theory of IP addressing is the prerequisite for building robust and scalable industrial networks.

When we look at a PLC rack communicating with a remote I/O block, we are seeing a conversation. Just as you need a specific street address to receive a package at your home, every device on an Ethernet/IP or Modbus TCP network needs a unique identifier to participate in this conversation. While MAC addresses are burned into the hardware at the factory, the IP address is something you, the engineer, must define and manage. This flexibility is powerful because it allows you to group devices logically by machine, cell, or entire production lines. As we transition from these theoretical concepts into our hands-on labs, you will see exactly how this logical addressing allows a laptop to communicate with multiple devices simultaneously through a single switch.

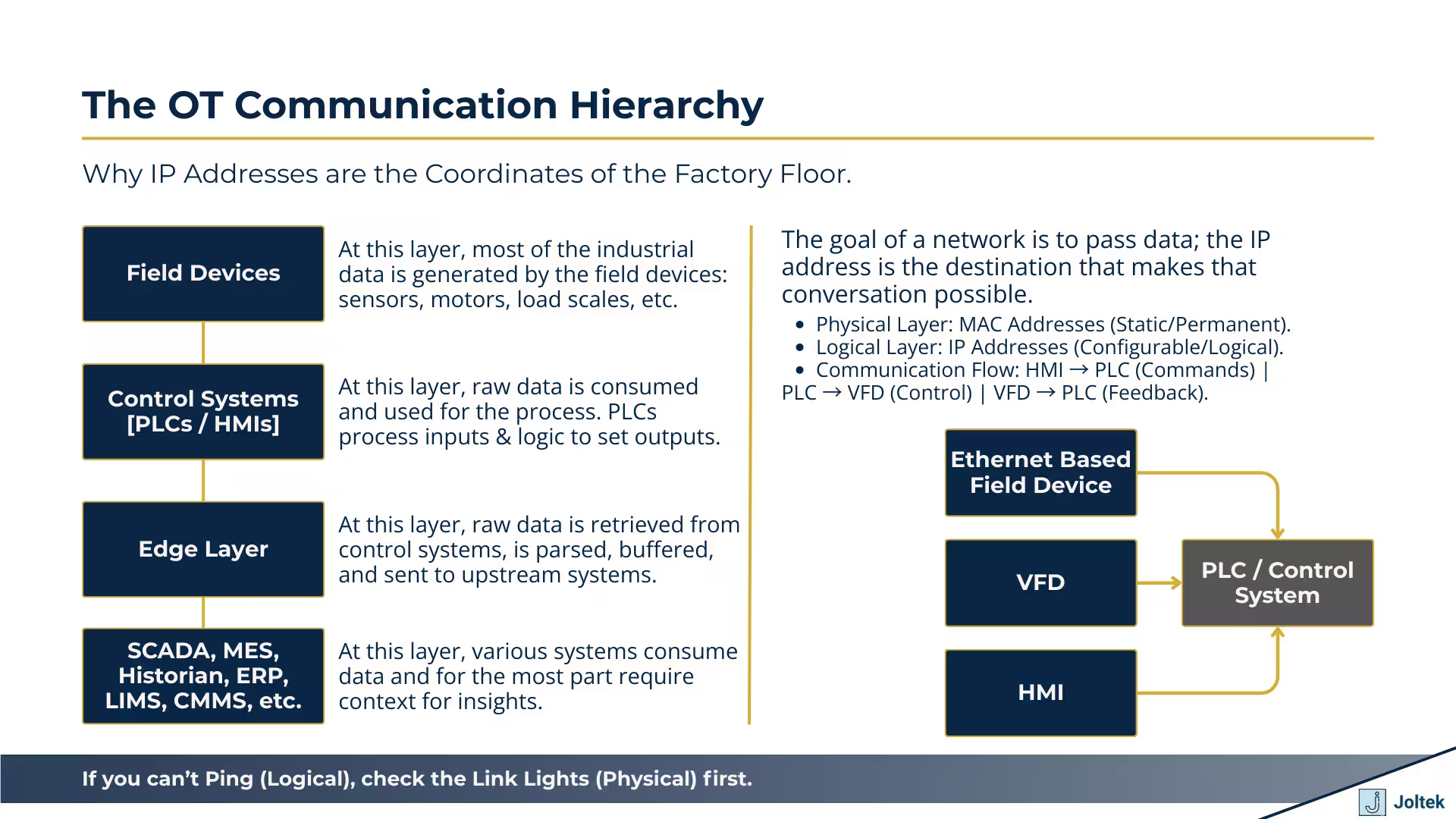

In the world of industrial automation, communication is the lifeblood of the system. Imagine a standard machine cell where a Programmable Logic Controller (PLC) serves as the brain, a Variable Frequency Drive (VFD) controls the motor speed, and an Human Machine Interface (HMI) provides the operator with real-time feedback. For these components to function as a cohesive unit, they must exchange thousands of data packets every second. While every piece of hardware comes with a permanent, factory assigned MAC address, these physical identifiers are not sufficient for complex routing. IP addresses provide the logical layer that allows us to organize these devices into a structured network. When a PLC sends a command to a VFD to increase its output frequency, it doesn't just broadcast that message to every device in the plant. Instead, it targets the specific IP address assigned to that drive. This level of precision is what prevents the network from being overwhelmed by unnecessary traffic and ensures that the right commands reach the right actuators at the exact millisecond they are needed.

The flow of information in an OT environment is typically a mix of cyclic and acyclic data. The PLC acts as the central hub, pulling status updates from the HMI and sending control parameters to the VFD. This exchange is entirely dependent on the logical addressing scheme you establish during the design phase. If you want an operator to be able to start or stop a machine from the HMI, that HMI must know the exact destination for its "Start" packet. Similarly, the PLC must be programmed with the address of the VFD to monitor its current, torque, and speed. Establishing a clear and documented IP addressing scheme is the only way to ensure seamless data flow across the different layers of your industrial architecture. This logical mapping allows engineers to swap out faulty hardware without having to rewrite the entire control program; as long as the new device is assigned the correct IP, the system can resume communication almost immediately.

Before diving into complex software configurations or protocol specific troubleshooting, the first tool in every automation professional's belt should be the ping command. This simple utility serves as a basic check to see if a destination device is reachable over the network. When you ping a device from your laptop, you are essentially sending a small request to its IP address and waiting for a response. If the device replies, you have confirmed that your physical cabling, the Ethernet switch, and the basic IP settings on both ends are functioning correctly. It is a critical first line of defense. If you cannot ping a VFD, there is no point in trying to configure its parameters via a web browser or software tool. By starting with a ping, you isolate the problem to the network layer before wasting time on application layer issues.

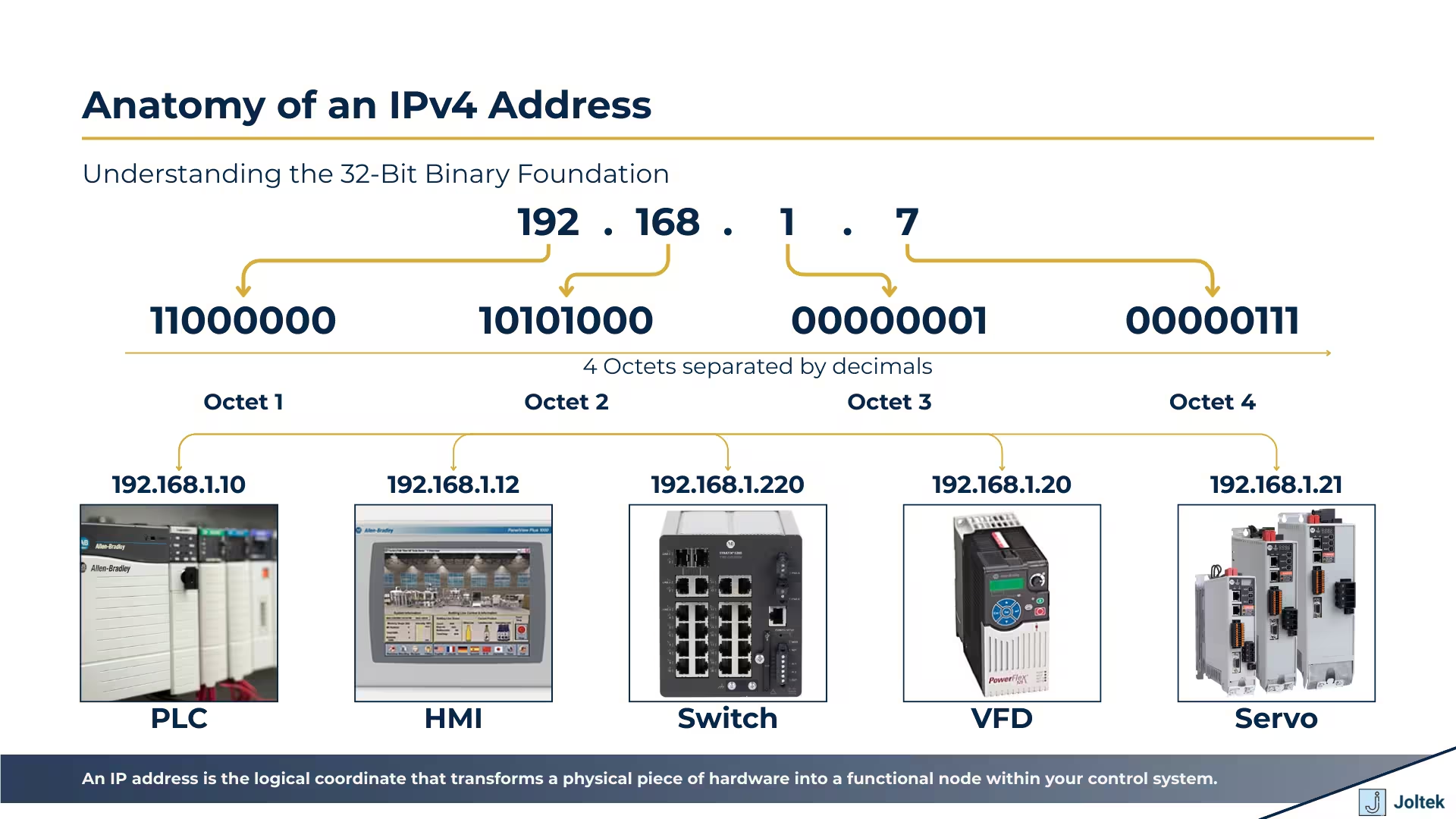

When you look at an IP address like 192.168.1.7, you are looking at a series of four numbers separated by dots. In technical terms, these are called octets. The reason they are called octets is because each of those four segments represents eight bits of binary data. In the binary world, eight bits can create 256 different combinations, which is why each segment of an IP address can only range from 0 to 255. While the computer sees a string of ones and zeros, we use the decimal representation to make it manageable for human engineers. Understanding this structure is the key to mastering network design because it dictates how many devices you can have and how they are grouped together on the factory floor.

The four octet structure is the backbone of IPv4, which is still the dominant standard in industrial automation. Each octet plays a role in defining the identity of a device. If you change even one digit in one of these octets, you are effectively moving that device to a different logical location. For example, a device at 192.168.1.10 cannot talk to a device at 192.168.2.10 unless there is a router or a specific gateway in between them. Every single device on your local subnet must have a unique IP address to prevent communication collisions that can crash a control system. This is why meticulous documentation is not just a good habit; it is a requirement for any reliable OT installation.

In the world of private networking, certain address ranges are reserved specifically for internal use. The most common range you will encounter in small to medium sized machine cells is the 192.168.x.x block. This range is popular because it is easy to remember and provides plenty of addresses for a typical industrial application. Many manufacturers even ship their hardware with default addresses in this range to make initial setup easier. For instance, when you are working with Industrial Ethernet Switches, you will often find that the management IP is pre configured to a standard address within the 192.168.x.x family.

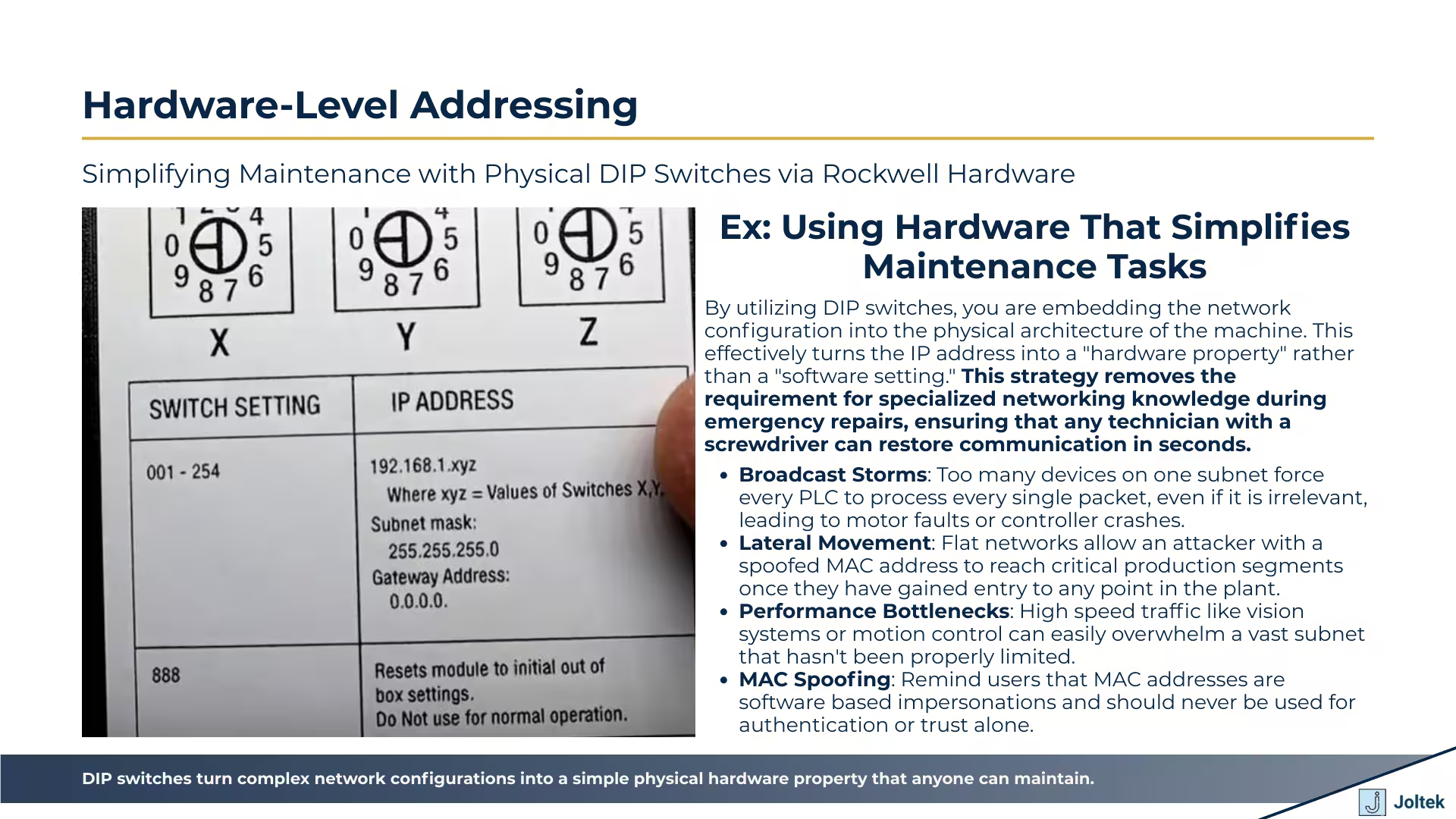

One of the unique aspects of OT networking compared to standard IT is how we sometimes set these addresses physically. On many Allen Bradley components, such as Point I/O modules or specific Ethernet cards, you will find a set of physical DIP switches. These switches usually allow you to set the value of the very last octet without ever opening a piece of software. If you set the switches to 105, the device automatically assumes an address like 192.168.1.105. This is a brilliant design for the plant floor because it allows a maintenance technician to swap out a failed module and set the correct address in seconds using nothing but a small screwdriver. It ensures that the "digital coordinates" are tied to the physical location of the hardware, making the system much easier to maintain over long periods.

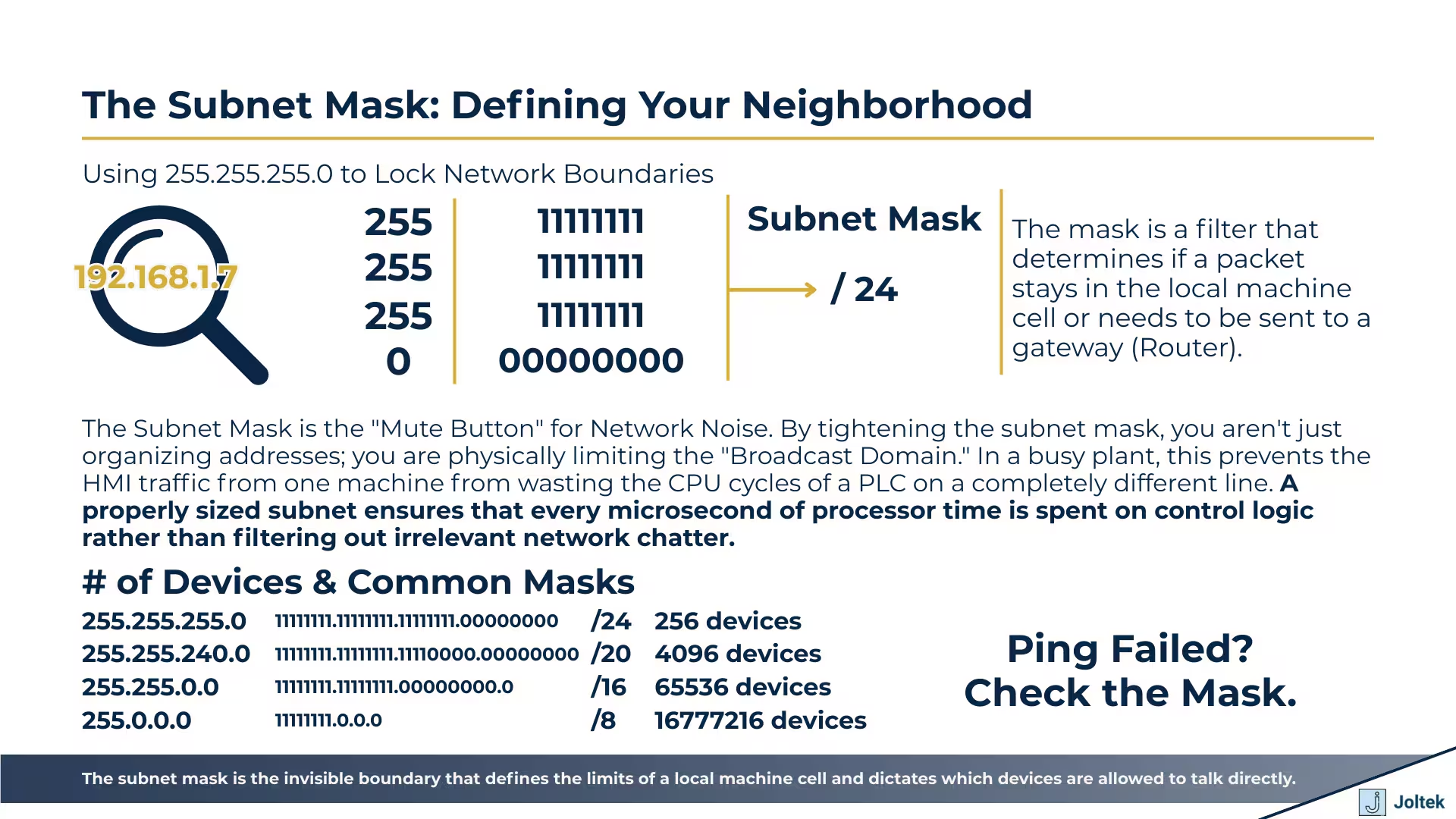

If the IP address is the street address of a device, the subnet mask is the tool that defines the boundaries of the neighborhood. In the industrial space, the subnet mask tells a device which other IP addresses are part of its local network and which ones are "outside" and require a gateway to reach. When you look at a standard configuration, you will almost always see the subnet mask 255.255.255.0 paired with an IP address. This mask effectively "locks" the first three octets, meaning any device you want to communicate with must share those same three numbers. Understanding this relationship is vital because a mismatch here is the most common reason for communication failure between a laptop and a PLC.

The subnet mask works through a process of binary logic to filter network traffic. When a PLC at 192.168.1.10 tries to send data to 192.168.1.20, it looks at its subnet mask. If the mask is 255.255.255.0, the PLC realizes that because the first three segments match exactly, the destination is local. It then sends the data directly across the switch. However, if the destination was 192.168.2.20, the PLC would see that the third octet does not match the "locked" portion of its mask and would realize it cannot talk to that device directly. The subnet mask is the fundamental mechanism that determines whether two industrial devices can communicate directly without the need for a router. This filtering is what allows us to keep local machine traffic separate from the rest of the plant network.

In many modern technical manuals and when talking to IT professionals, you might see a shorthand version of the subnet mask known as Classless Inter-Domain Routing (CIDR) notation. Instead of writing out 255.255.255.0, they will simply write a forward slash followed by the number of bits that are "masked" or set to one. For example, a standard mask is written as /24 because there are 24 bits (three octets of eight bits each) that are locked. If you see /16, it means only the first two octets are locked, which opens up a massive number of available addresses. While it may seem like a minor detail, being able to translate between decimal and CIDR notation is a key skill when you are configuring high end Industrial NAT Routers or managing complex network documentation.

A standard /24 or 255.255.255.0 subnet provides 254 usable addresses for your devices. For a single machine or a small production cell, this is more than enough. However, as factories become more connected, you might find yourself in a situation where you need hundreds or even thousands of addresses on a single logical network. By changing the subnet mask: for example, to 255.255.0.0; you stop locking that third octet. This simple change expands your available pool from 254 addresses to over 65,000. While this sounds powerful, it comes with significant risks regarding network performance and traffic management, which is why we generally prefer smaller, more manageable subnets on the plant floor.

Managing an industrial network requires a higher level of discipline than a standard office environment. In an OT setting, stability is everything. When you are assigning addresses, you have to think about more than just connectivity; you have to think about long term maintainability and security. A common mistake is treating the network as a "set it and forget it" task. In reality, as soon as you add a second or third device, you are building an infrastructure that needs a clear set of rules. Implementing a rigid IP addressing standard across your facility is the most effective way to prevent accidental downtime caused by IP conflicts. This means moving away from random assignments and toward a structured plan that every technician and engineer follows.

One of the most important rules in networking is that no two devices can share the same IP address. If you accidentally assign your laptop the same address as a critical PLC, you will cause a conflict that can drop the PLC offline or disrupt its communication with I/O modules. Furthermore, you must respect reserved addresses. The .0 address is used to identify the network itself, while .255 is the broadcast address used to send data to every device on the subnet simultaneously. Most importantly, the .1 address is almost always reserved for the Gateway. The Gateway is the "exit door" for your network, usually an Industrial Ethernet Switch or a router that connects your machine cell to the rest of the plant. Avoiding these specific numbers ensures your network remains compatible with standard routing hardware.

It can be tempting to set a very wide subnet mask like 0.0.0.0 to avoid ever having to worry about subnets again. In theory, this would allow every device to talk to every other device regardless of their IP. However, this is a dangerous practice on the factory floor. Industrial protocols like EtherNet/IP rely heavily on multicast and broadcast traffic to function. If your subnet is too large, the amount of background "noise" or "broadcast storms" can overwhelm the processing power of smaller devices like VFDs or sensors. By keeping your subnets small and focused: typically a /24 or 255.255.255.0; you ensure that high speed motion control or vision system traffic doesn't interfere with other parts of the plant. Keeping the pool small also reduces the "attack surface," making it harder for unauthorized devices to interact with your controllers.

Understanding IP addresses and subnet masks is the bridge between being a technician who just "plugs things in" and an automation engineer who designs resilient systems. We have seen how these digital coordinates allow our PLCs, HMIs, and drives to communicate with precision, and how the subnet mask acts as a vital filter for that traffic. By following the standards of private networking and respecting the math behind the octets, you can build networks that are both high performing and easy to troubleshoot.

As we move from this theory into our practical labs, keep these fundamentals in mind. Whether you are using physical DIP switches or sophisticated software to commission your hardware, the logic remains the same. A unique IP, a matching subnet mask, and a clear understanding of your network boundaries are all you need to ensure your data gets exactly where it needs to go. If you are looking to dive deeper into the physical hardware that makes this possible, be sure to check out our Ultimate Guide to Allen Bradley PLCs to see how these concepts are applied in real world hardware configurations.