Introduction

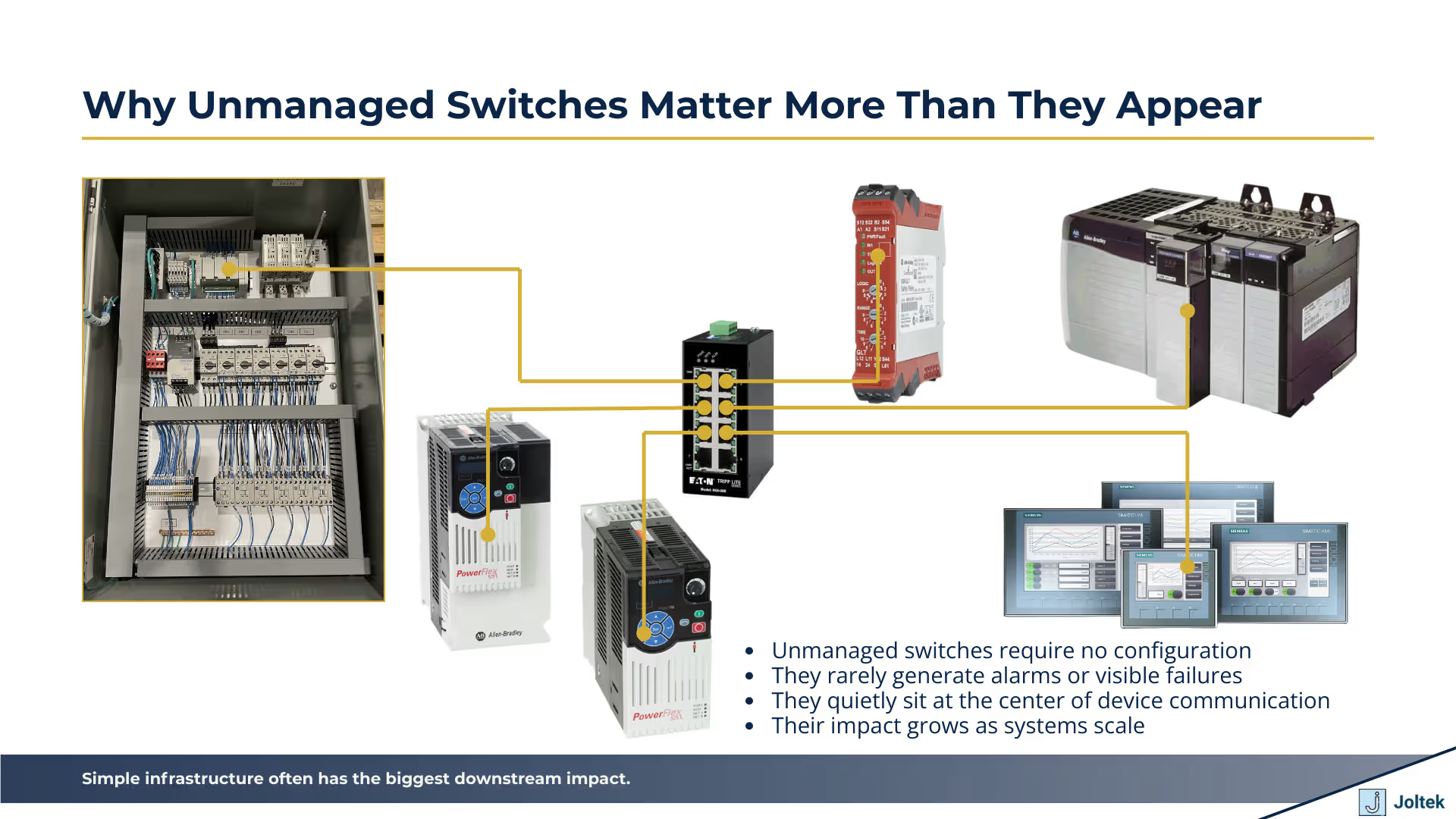

Unmanaged switches are one of those components that almost disappear once they are installed. They do not require configuration, they do not expose dashboards, and they rarely generate alarms. For many engineers, especially early in their careers, they feel like a solved problem. Plug the cables in, confirm link lights, assign IP addresses, and move on. That simplicity is exactly why unmanaged switches deserve far more attention than they usually receive. In OT environments, these devices quietly influence how reliable a system feels during normal operation, how well it scales when new equipment is added, and how exposed it becomes when something unexpected happens.

On the plant floor, networks are not abstract concepts. They directly affect whether a PLC can reliably control a drive, whether an HMI responds instantly to operator input, and whether troubleshooting takes minutes or hours during downtime. Unmanaged switches sit at the center of many of these interactions, forwarding traffic between PLCs, HMIs, VFDs, remote IO, and laptops without discrimination or awareness. In a lab or small demo setup, this behavior feels harmless and often beneficial. In a production environment, the same behavior can amplify broadcast traffic, hide early warning signs of network stress, and remove any meaningful control over who or what is allowed to communicate.

Unmanaged switches matter precisely because they do not make decisions, and that lack of decision making shapes everything built on top of them.

This article is meant to bridge the gap between lab level understanding and real production realities. Many engineers first encounter unmanaged switches while learning basic OT networking concepts such as IP addressing, MAC addresses, and subnetting. Those fundamentals are critical, but they only tell part of the story. Once systems grow, once multiple machines share a subnet, and once uptime and cybersecurity become business concerns rather than academic ones, the role of a simple switch becomes much more nuanced. If you are looking to place unmanaged switches in context within a broader OT architecture conversation, including how they interact with reliability and risk, this aligns closely with how we think about plant networks during assessments and modernization efforts at Joltek, particularly in the context of IT and OT architecture integration found here https://www.joltek.com/services/service-details-it-ot-architecture-integration.

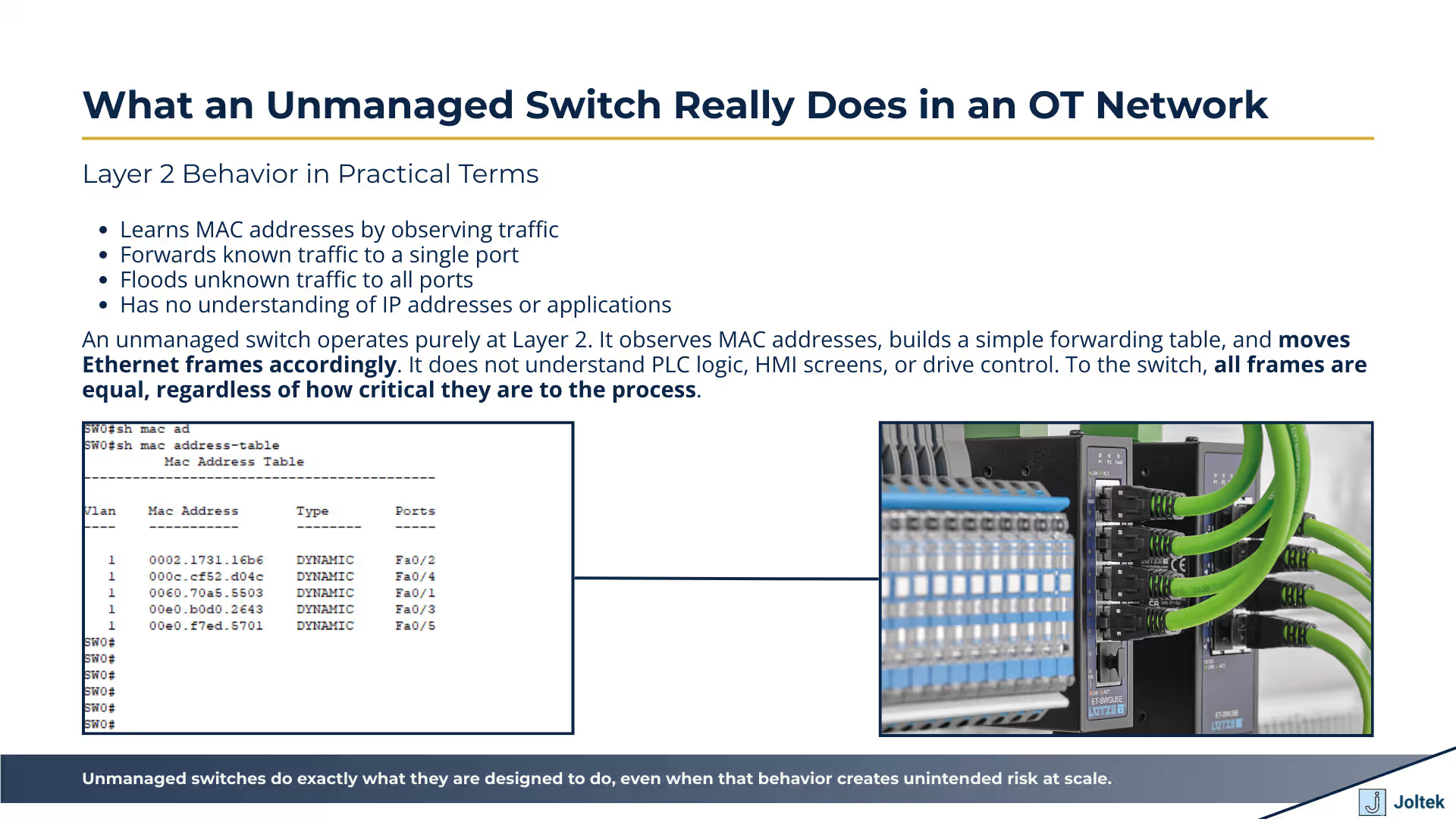

At its core, an unmanaged switch is a Layer 2 device whose job is to move Ethernet frames from one port to another based on MAC addresses. When a PLC sends a frame toward an HMI, a VFD, or another controller on the same subnet, that frame includes a source MAC address and a destination MAC address. The switch listens to traffic as it passes through, learns which MAC addresses are reachable on which physical ports, and builds a simple internal table to make forwarding decisions. If the destination MAC address is known, the frame is forwarded only to the appropriate port. If it is unknown, the switch floods the frame out of all ports except the one it came from.

In practical OT terms, this means that a PLC, an HMI, multiple drives, and even an engineering laptop can all coexist on the same physical network without needing direct point to point cabling between every device. The switch becomes the shared communication fabric inside the panel or across a machine. There is no understanding of IP addresses, control logic, or application data at this level. The switch only sees frames and MAC addresses. That simplicity is powerful because it removes configuration overhead, but it also means the switch has no awareness of what traffic matters more, which devices are critical, or how often certain messages should be exchanged.

When traffic levels are low and the number of devices is small, unmanaged switches tend to fade into the background. PLC scan times remain stable, HMIs feel responsive, and drives behave exactly as expected. Because there is nothing to configure and nothing to monitor, engineers often treat the switch as a passive component rather than an active part of the control system. As long as link lights are on and devices respond to pings, the network is assumed to be healthy.

This invisibility creates a false sense of simplicity. As systems grow, additional devices are added, firmware changes introduce new communication patterns, or temporary laptops are connected during commissioning, the switch continues to behave the same way. It forwards frames and floods unknown traffic without complaint. The lack of feedback makes it difficult to recognize early warning signs. Problems rarely appear gradually. Instead, they surface during scale, during abnormal conditions, or during troubleshooting when timing suddenly matters and there is no easy way to see what the network is doing internally.

One of the most important characteristics of unmanaged switches is how they handle broadcast and multicast traffic. Broadcast frames are sent to every device on the subnet by design. Multicast traffic, which is commonly used by Ethernet based industrial protocols, is often treated similarly by unmanaged switches unless special handling is supported. Protocols such as Ethernet IP rely on periodic messaging, discovery traffic, and implicit connections that can generate a steady stream of frames even when the process appears idle.

Unmanaged switches forward this traffic to all connected ports, regardless of whether the receiving devices care about it. PLCs must process incoming frames, decide whether they are relevant, and then discard what they do not need. Drives and IO devices do the same. As traffic increases, this background processing can start to matter. PLC scan times can stretch, drive responsiveness can feel inconsistent, and HMIs may exhibit subtle delays or missed updates. These effects are often blamed on controllers or firmware when the underlying issue is simply that the network is doing exactly what it was built to do without any prioritization or filtering.

Unmanaged switches do exactly what they are designed to do, even when that behavior creates unintended risk at scale.

Manufacturing environments impose stresses that rarely exist in offices, labs, or home setups. Inside a control panel, temperatures can fluctuate widely depending on ambient conditions, heat generated by drives and power supplies, and whether cooling is active or passive. Vibration from motors, conveyors, and nearby machinery is transmitted through enclosures and mounting rails. Electrical noise from high current switching devices, variable frequency drives, and contactors is constantly present. Grounding quality varies from plant to plant and is often far from ideal. Industrial grade switches are designed with these realities in mind, using components and layouts that tolerate heat, reject noise, and continue operating reliably in less than perfect electrical conditions.

Commercial switches are built for climate controlled spaces where temperature is stable, vibration is minimal, and power quality is relatively clean. When placed in a control panel, they are exposed to conditions they were never designed to handle for extended periods of time. The result is not always immediate failure. More often it shows up as intermittent behavior, random lockups, or degraded performance after months or years of operation. In manufacturing, long term uptime expectations are measured in years, not in the typical replacement cycles seen in office IT equipment. That difference alone fundamentally changes how network components should be selected.

The physical design of an industrial switch is just as important as its electrical characteristics. DIN rail mounting allows switches to be secured properly within panels alongside PLCs, power supplies, and IO. This mounting method is not just about convenience. It ensures consistent grounding, predictable airflow paths, and resistance to vibration. Industrial switches are typically designed for passive cooling, relying on heat sinks and enclosure design rather than small internal fans that can clog or fail over time.

Connector retention is another critical factor. Ethernet cables on the plant floor are often subject to movement during maintenance, troubleshooting, or panel modifications. Industrial switches use connectors and port housings designed to maintain solid contact even when cables are disturbed. In dense panels, where multiple cables are routed tightly together, this robustness reduces the risk of intermittent faults that are notoriously difficult to diagnose. From a maintenance perspective, equipment that stays firmly mounted and connected reduces both downtime and the time required to safely work inside energized panels.

One of the most overlooked differences between industrial and commercial switches is lifecycle expectation. Industrial hardware is selected with the assumption that it will remain in service for many years, often aligned with the lifecycle of the machine or production line itself. Manufacturers of industrial switches publish long term availability commitments, support firmware over extended periods, and design products to meet conservative MTBF targets. When failures do occur, they are typically predictable and gradual, allowing maintenance teams to plan replacements.

By contrast, commercial switches follow short product cycles driven by consumer and enterprise markets. Models are discontinued quickly, components change frequently, and long term support is not guaranteed. When a commercial switch fails on the plant floor, replacing it is not equivalent to swapping a device at home. Access to the panel may require downtime, safety procedures, and coordination across teams. The cost of that interruption often dwarfs the price difference between the two types of hardware.

The price difference reflects survivability, not performance.

Most engineers first encounter unmanaged switches when a simple point to point connection is no longer enough. A PLC connected directly to a VFD works well for basic control and commissioning, but the moment an HMI is introduced, the limitations of single cable connections become obvious. The switch becomes the meeting point that allows the PLC, the HMI, and the drive to exchange data concurrently while still giving an engineer the ability to connect a laptop for configuration or troubleshooting. At this stage, unmanaged switches feel like an elegant solution that removes physical constraints without adding complexity.

As systems evolve, additional devices quickly enter the picture. Remote IO racks appear to reduce wiring. Additional drives are added to support new motors. Vision systems, barcode readers, robots, and safety devices begin to share the same subnet. Each new device brings its own communication patterns, update rates, and background traffic. The unmanaged switch continues to forward everything without discrimination. From the outside, the architecture still looks simple. From the inside, the network has quietly shifted from a handful of predictable conversations to a shared medium carrying many simultaneous exchanges with very different timing sensitivities.

When port counts are exhausted, the most common response is to add another unmanaged switch and connect it to the first one. This approach is intuitive and often encouraged by how inexpensive and easy unmanaged hardware is to deploy. Functionally, it works because unmanaged switches treat the interconnection just like another port. Traffic flows freely across both devices, and all connected endpoints remain on the same subnet.

What changes is not obvious until problems appear. Every additional switch increases the physical distance that frames must travel and expands the broadcast domain. Broadcast and multicast traffic is forwarded across every link, reaching devices that may not need to see it at all. Latency increases slightly at each hop, usually staying below any threshold that triggers alarms or faults. Because there is no visibility into port utilization or error rates, there is no clear signal that the network is becoming saturated. The architecture works smoothly until a new device is added, a firmware update alters traffic patterns, or a temporary engineering laptop introduces unexpected chatter. At that point, diagnosing the root cause becomes difficult because the network offers no insight into what changed.

One of the challenges with unmanaged switches is that their limits are rarely defined in terms that matter on the plant floor. Datasheets list port counts and basic throughput, but they do not describe how the device behaves under sustained multicast traffic, high packet rates, or mixed protocol environments. Industrial protocols vary widely in how chatty they are. Some rely on frequent cyclic updates, others on event driven messaging, and some combine both. Firmware versions on PLCs, drives, and third party devices can dramatically change traffic patterns without any visible change to the control logic.

In practice, the constraint is rarely the number of ports. It is the cumulative effect of packet rates, background discovery traffic, and protocol behavior interacting in ways that unmanaged switches cannot moderate or prioritize. Two networks with the same number of devices can behave very differently depending on vendor implementations and configuration defaults. This is why scaling unmanaged networks often feels unpredictable and why issues are sometimes misattributed to controllers or applications rather than the underlying communication fabric. Understanding these dynamics is critical when evaluating broader plant architectures and risk, which is why unmanaged networks frequently surface as a hidden concern during deeper reviews such as those discussed in Joltek’s work around industrial cybersecurity and network exposure at https://www.joltek.com/blog/industrial-cybersecurity-ics.

Unmanaged networks fail gradually and then all at once.

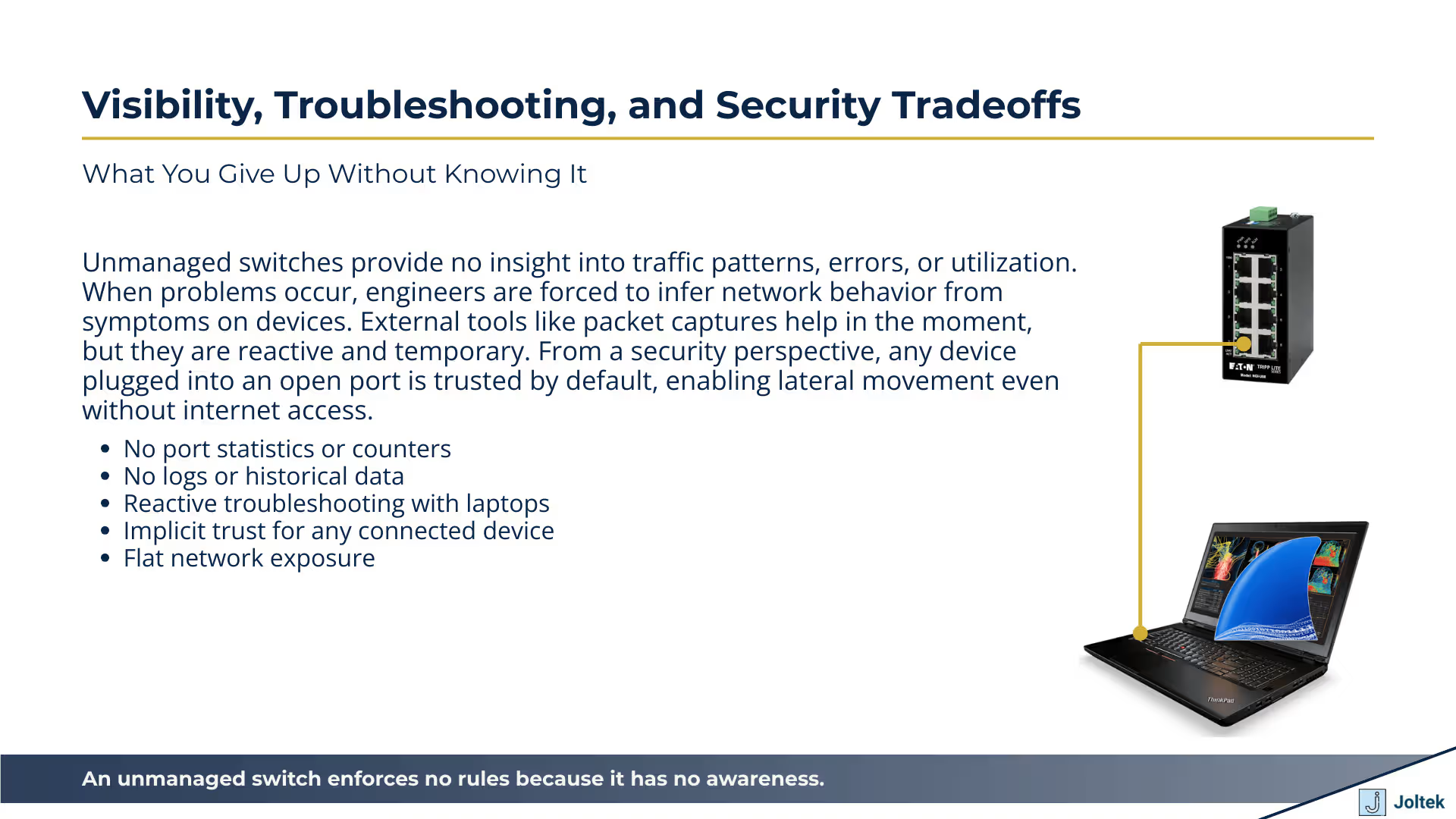

Unmanaged switches provide no native visibility into what is happening inside the network. There are no counters showing port utilization, no logs capturing errors, no indicators of dropped frames, and no way to understand traffic patterns over time. From the perspective of the switch, everything is treated equally and silently forwarded. For engineers working on the plant floor, this creates a gap between how problems actually occur and how they are forced to troubleshoot them. When downtime hits, the expectation is to identify root cause quickly, isolate the issue, and restore production. With unmanaged switches, the network itself offers no clues. Engineers are left inferring behavior based on symptoms observed at PLCs, HMIs, and field devices rather than seeing what the network is doing directly.

Under pressure, troubleshooting tends to become device centric rather than system centric. A slow HMI is blamed on the HMI. A delayed drive response is blamed on the drive or the PLC. Network cables get swapped, devices get power cycled, and configuration changes are rolled back in hopes that something sticks. The lack of visibility encourages trial and error rather than informed decision making. In many cases, the network is the contributing factor, but it remains invisible because the switch offers no way to confirm or disprove that hypothesis.

To compensate for this blind spot, engineers rely on external tools. Packet capture software such as Wireshark is often used by connecting a laptop to an available port and monitoring traffic in real time. PLC diagnostics may expose basic statistics about communication load or connection status. Temporary connections are made during commissioning or troubleshooting to observe behavior under live conditions. These techniques can be powerful, but they are inherently reactive.

They require time, access, and expertise, and they are typically applied only after a problem has already impacted production. Packet captures represent a snapshot in time rather than a continuous record. PLC diagnostics vary widely by vendor and rarely provide a complete picture of network health. Temporary laptops introduce additional traffic and complexity into an already stressed system. While these tools are valuable, they do not replace having built in visibility at the network layer. They help answer what is happening right now, but they do little to explain what changed over weeks, months, or years as the system evolved.

One of the most misunderstood aspects of unmanaged switches is their role in cybersecurity. In many OT environments, the assumption is that physical access is the primary line of defense. If someone cannot reach the panel, the network is considered secure. Unmanaged switches reinforce this mindset because they impose no authentication, no segmentation, and no traffic rules. Any device plugged into an open port is treated as trusted by default. That trust extends to all other devices on the subnet.

In modern threat models, this implicit trust is increasingly risky. Insider threats, contractor access, and well intentioned but unvetted devices can introduce exposure without any internet connection involved. Flat networks allow unrestricted lateral movement once access is gained. Even benign actions such as connecting a misconfigured laptop can disrupt communication or expose sensitive control traffic. These risks are often uncovered during deeper architectural reviews and assessments, where network design is evaluated not just for functionality but for resilience and risk. This is a common theme in broader discussions around control system architecture and modernization, including how network visibility and segmentation factor into long term reliability as explored in https://www.joltek.com/blog/manufacturing-plant-audit-digital-transformation.

An unmanaged switch enforces no rules because it has no awareness.

Unmanaged switches absolutely have a place in OT networks. They make sense in small, contained systems where device counts are limited, traffic patterns are well understood, and the risk profile is low. They are useful in labs, training environments, temporary setups, and simple machines where the network is not expected to grow or change significantly over time. In those contexts, their simplicity is an advantage. Fewer configuration steps mean fewer opportunities for misconfiguration, and lower cost can be justified when the consequences of failure are minimal.

Problems arise when unmanaged switches are treated as neutral building blocks rather than active architectural decisions. As networks scale, as more devices share the same subnet, and as uptime and cybersecurity expectations increase, the very characteristics that make unmanaged switches attractive begin to work against the system. Lack of visibility, lack of control, and implicit trust become liabilities rather than conveniences. These issues rarely announce themselves early. They surface later, often during downtime, expansion, or incident response, when options are limited and pressure is high.

The key shift for engineers and technical leaders is to think architecturally rather than tactically. A switch is not just a way to add ports. It is part of the communication fabric that ties control logic, operator interfaces, drives, and field devices together. Decisions made at this layer influence reliability, troubleshooting effort, and risk exposure long after installation. Treating switching decisions as system design decisions rather than purchasing shortcuts changes how networks are built and how they age over time.

This article lays the groundwork for that mindset. From here, the natural progression is to explore how managed switches introduce visibility, control, and segmentation, and how those capabilities fit into secure and scalable OT architectures. Understanding unmanaged switches clearly is the first step toward knowing when they are appropriate and when the system has outgrown them.

Unmanaged switches are not wrong choices, but they are rarely neutral ones.