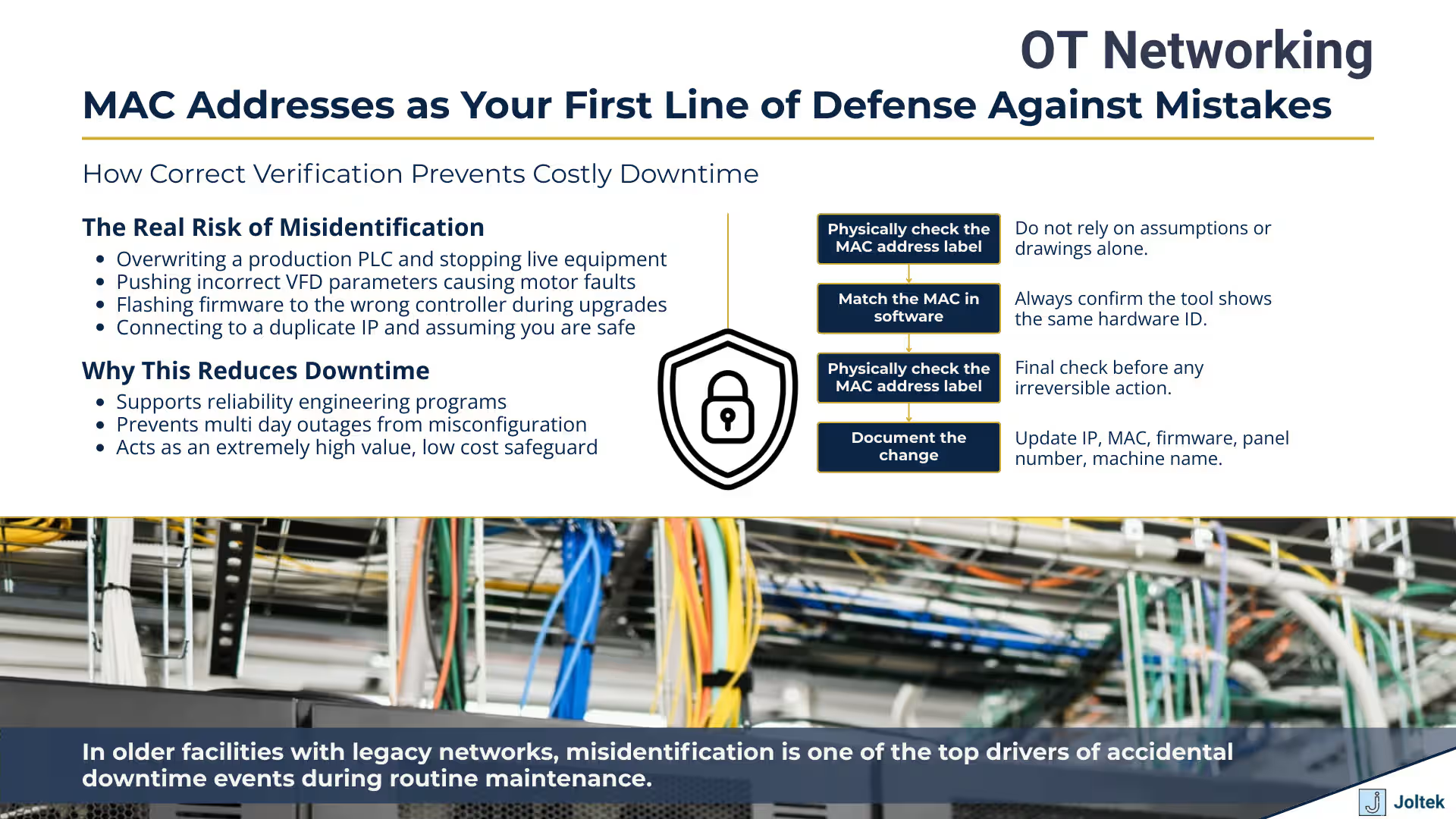

If you've spent any time working on industrial networks, you've probably encountered a moment of panic when connecting to plant floor equipment. You plug into a switch, open your configuration software, and suddenly you're looking at a dozen devices with IP addresses you don't recognize. Which one is the HMI you need to configure? Which one is the PLC that's currently running production? Making the wrong choice doesn't just waste time; it can shut down an entire production line or overwrite critical programs that took weeks to develop.

This is where MAC addresses become absolutely essential. While IP addresses can be changed by anyone with the right access, MAC addresses are permanent hardware identifiers burned into every network interface during manufacturing. In operational technology environments, where a single configuration mistake can cost thousands of dollars in downtime, understanding MAC addresses isn't just helpful; it's a fundamental requirement for safe and effective engineering work.

Most discussions about MAC addresses focus on theory. You'll read about hexadecimal formats, organizationally unique identifiers, and how manufacturers assign these addresses. That's all fine for networking certification exams, but it misses the practical reality that OT engineers face every day. The truth is, MAC addresses matter most during those critical moments when you're standing in front of a control panel with a laptop, trying to commission new equipment or troubleshoot a live system without accidentally connecting to the wrong device.

This is exactly what engineers deal with in the field. When you're commissioning a new machine with multiple PLCs, VFDs, and HMIs all connected through a switch, you need a reliable way to identify which device you're actually configuring. The consequences of getting it wrong range from embarrassing (spending an hour troubleshooting why your changes didn't take effect) to catastrophic (overwriting the program on a production PLC). This has happened more often than anyone wants to admit, especially with legacy protocols where device identification was less sophisticated than it is today.

In this post, we're going beyond the textbook definitions. We'll explore how MAC addresses function as your safety net during commissioning, how they help prevent configuration disasters, and why they're becoming increasingly important as OT networks converge with IT infrastructure and face new security challenges. Whether you're working directly on plant floor OT networking or managing broader digital transformation initiatives, understanding MAC addresses at a practical level will make you more effective and more confident in your work.

This isn't about memorizing hexadecimal formats or understanding IEEE registration standards. This is about knowing what to do when you walk up to a control panel with your laptop and need to configure devices safely and correctly. It's about developing the habits that separate engineers who accidentally shut down production from those who commission equipment reliably every single time.

The most important thing to understand about MAC addresses is that they're fundamentally different from IP addresses in ways that directly impact how you work with industrial equipment. An IP address is a logical identifier assigned through software configuration. You can change it whenever you need to, whether that's because you're moving equipment to a different network segment, reorganizing your plant architecture, or resolving an address conflict. MAC addresses, by contrast, are physical identifiers burned into the hardware during manufacturing and cannot be changed through normal configuration processes. This permanence is what makes them so valuable for device identification in OT environments.

When you configure an IP address on a PLC or VFD, you're essentially telling that device how it should identify itself on a particular network at layer three of the OSI model. Change the IP address and the device immediately adopts its new identity. The MAC address operates at layer two, the data link layer, and it stays constant regardless of what network the device connects to or what IP address you assign. Think of the IP address as a mailing address that changes when you move, while the MAC address is more like a serial number etched into the device itself. This distinction becomes critical when you're working in environments where devices might be relocated, networks are being restructured, or you're simply trying to verify that you're connected to the correct piece of equipment before making configuration changes.

The format of a MAC address reflects its purpose as a globally unique identifier. You'll see six groups of hexadecimal digits, typically written as 00:1A:2B:3C:4D:5E or sometimes with periods or hyphens as separators depending on the manufacturer's labeling convention. Each pair of hexadecimal digits represents one octet or byte, giving you 48 bits of addressing space total. This format can look intimidating at first, especially if you're more comfortable with the decimal notation used in IP addresses, but you don't need to convert these values or perform calculations with them. What matters is that you can read them accurately, write them down without transposing digits, and match them between physical labels and software displays.

The assignment of MAC addresses follows a structured system managed by the IEEE Registration Authority. When a manufacturer wants to produce network capable devices, they purchase blocks of MAC addresses from the IEEE. The first three octets, known as the Organizationally Unique Identifier or OUI, identify the manufacturer. The last three octets are assigned by that manufacturer to individual devices. This means that when you look at a MAC address like 00:00:BC:12:34:56, those first three octets (00:00:BC) tell you this device was manufactured by Allen-Bradley, which is now part of Rockwell Automation. Different manufacturers have different OUIs, and larger manufacturers often have multiple OUI blocks as they produce millions of devices over time. While you don't need to memorize these manufacturer codes, understanding that they exist helps you recognize patterns when you're working with equipment from the same vendor or troubleshooting networks where multiple manufacturers' devices coexist.

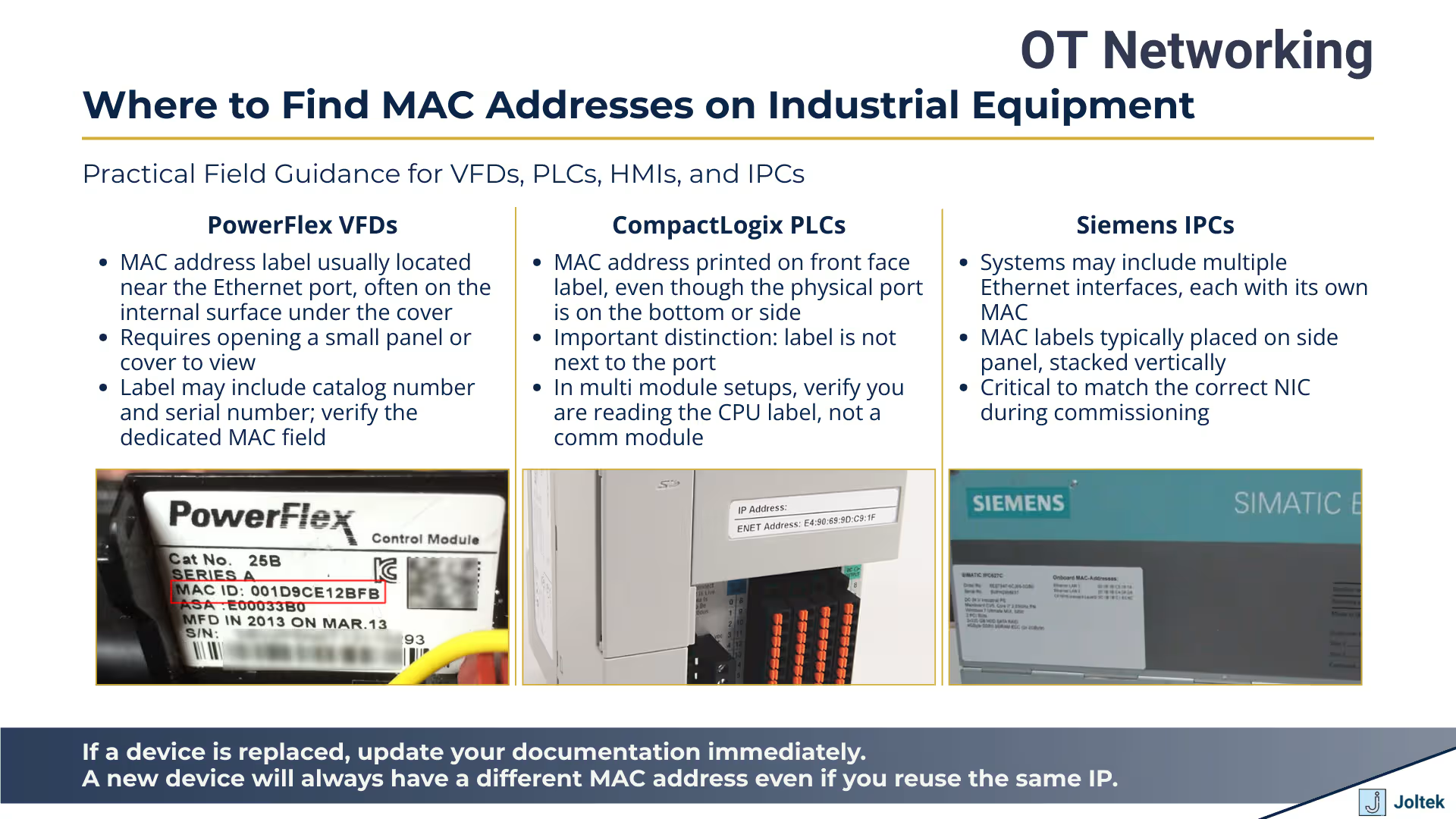

Locating the MAC address on industrial equipment is one of those tasks that seems straightforward until you're actually standing in front of a control panel trying to find it. Unlike consumer electronics where the MAC address might be buried in a settings menu, industrial devices typically display this information on a physical label somewhere on the equipment housing. The challenge is that there's no universal standard for where manufacturers place these labels, and the location can vary significantly not just between vendors but even between product lines from the same manufacturer.

On PowerFlex VFDs from Rockwell Automation, you'll typically find the MAC address label on an internal surface near the Ethernet port itself. This makes sense from an engineering perspective because it keeps the information close to the physical interface it describes, but it also means you might need to remove a cover or access panel to read it. The label will usually include other identifying information like the catalog number and serial number, but the MAC address is specifically called out, often with "MAC" or "Ethernet Address" printed above the hexadecimal digits. When you're commissioning new equipment, this placement near the port is actually helpful because you can verify you're looking at the right label for the right interface, especially on devices that might have multiple network connections.

CompactLogix PLCs take a different approach. These controllers often have the MAC address printed on a label affixed to the front of the device, while the actual Ethernet port is located on the bottom or side of the chassis. This separation between the label and the physical port can be confusing initially, but it reflects the reality that the front of a PLC is usually more accessible once the device is mounted in a panel. You can read the MAC address without reaching around or behind the equipment to see the port itself. The trade off is that you need to be more careful about matching labels to ports on systems where you might have multiple PLCs or communication modules in the same rack.

Siemens takes yet another approach with their industrial PCs and automation equipment. On many Siemens IPCs, you'll find a label on the side of the device that lists multiple pieces of information including the MAC address for each network interface if the device has more than one. This is particularly important to note because modern industrial computers often have two or more Ethernet ports, and each one has its own unique MAC address. The physical placement of MAC address labels matters most during commissioning because you need to be able to read them while standing in front of equipment that may be mounted in racks, installed in tight spaces, or positioned where only certain surfaces are visible. Taking the time to locate and document these labels before you start configuring addresses prevents the frustration of having to shut down equipment or partially disassemble panels later just to verify which device you're working with.

Beyond just finding the label, you need to develop a system for documenting MAC addresses as you work. Some engineers take photos of the labels with their phones, which creates a timestamped record that also captures the physical context of where the device is installed. Others maintain notebooks where they write down the MAC address alongside other identifying information like the device location, IP address, and cabinet number. The specific method matters less than the consistency. When you're standing in front of a switch looking at multiple devices that all appear on the network, having an accurate record of which MAC addresses correspond to which physical equipment is the only reliable way to ensure you're configuring the correct device.

This documentation becomes even more critical in scenarios where equipment might be swapped out or replaced during maintenance. If a VFD fails and needs to be replaced with a new unit, the replacement will have a different MAC address even if you configure it with the same IP address as the original. Any documentation or network management tools that tracked the old MAC address now need to be updated. This is why many facilities maintain asset management databases that record both the current IP address and MAC address for every networked device, along with information about when devices were installed or replaced. The MAC address becomes part of the permanent record for that equipment location, even as the physical device occupying that position might change over time.

The internal structure of a MAC address carries information that can be genuinely useful when you're working in complex industrial environments, even though you're not performing any calculations or conversions with these values. Those first three octets that make up the Organizationally Unique Identifier serve as a fingerprint for the manufacturer, and recognizing patterns in these OUIs can help you identify equipment faster when you're scanning networks or reviewing device lists in configuration software.

For instance, if you're working in a facility that primarily uses Rockwell Automation equipment, you'll start to recognize OUIs like 00:00:BC and similar patterns that indicate Allen-Bradley or Rockwell hardware. When you scan a network and see a MAC address that doesn't match these familiar patterns, it immediately tells you this might be a device from a different vendor, perhaps a Siemens drive, a Schneider Electric PLC, or even a standard IT device like a network printer that someone connected to the industrial network. This pattern recognition isn't about memorizing long lists of manufacturer codes; it's about developing familiarity with the equipment you work with regularly so that outliers become obvious.

The last three octets, which the manufacturer assigns to individual devices, generally follow sequential patterns as devices come off production lines. You might notice that VFDs purchased as part of the same order have MAC addresses where those last three octets increment sequentially, like ending in 12:34:56, then 12:34:57, then 12:34:58. This sequential assignment doesn't have practical implications for how you configure the devices, but it can help you verify that multiple devices came from the same production batch or purchase order, which might be relevant for inventory management or warranty tracking.

Understanding this structure also helps when you're dealing with network diagnostic tools and managed switches. Many industrial Ethernet switches can display connected devices by MAC address, and they'll show you which physical port each MAC address appears on. When you're troubleshooting connectivity issues or trying to map out an undocumented network, being able to correlate the MAC addresses you see in the switch interface with the manufacturer information embedded in those first three octets gives you a much clearer picture of what's actually connected and where. You can distinguish between a legitimate industrial device and something that shouldn't be on that network segment, like a personal laptop or an unauthorized wireless access point.

The global uniqueness of MAC addresses is maintained through this two part structure. With the IEEE allocating OUI blocks to manufacturers and each manufacturer maintaining their own assignment process for the device specific portion, the system ensures that no two network interfaces should ever have the same MAC address. This uniqueness is what allows MAC addresses to function reliably for device identification across networks of any size. In theory, you could have devices from dozens of manufacturers all connected to the same switch, and as long as they each have a properly assigned MAC address, there should be no conflicts at layer two. In practice, this theoretical uniqueness does face challenges through MAC address spoofing and misconfigured devices, but understanding that the structure is designed to guarantee uniqueness helps you recognize when something has gone wrong and a duplicate MAC address appears on your network.

When we talk about MAC addresses as permanent identifiers, we need to be honest about an uncomfortable reality: while MAC addresses are burned into hardware at the factory, they can be spoofed through software. MAC address spoofing is the process of changing the MAC address that a network interface reports to the network, effectively allowing one device to impersonate another. On most modern operating systems, this requires nothing more than administrative privileges and a few commands. An attacker with access to a laptop and basic networking knowledge can configure their network adapter to broadcast any MAC address they choose, including one that belongs to a legitimate device on your industrial network.

The mechanics of MAC spoofing are straightforward enough that they should concern anyone responsible for OT security. When a device connects to a network, it announces its presence using its MAC address at layer two. Switches use these MAC addresses to build forwarding tables that determine which physical port corresponds to which device. If an attacker spoofs the MAC address of a trusted device, they can potentially intercept traffic intended for that device, bypass basic access controls that rely on MAC filtering, or cause confusion in the network by creating duplicate MAC address scenarios. The vulnerability is particularly acute in OT environments because many industrial protocols were designed decades ago with the assumption that all devices on the network were physically secured and trusted. These protocols often lack the authentication mechanisms that modern IT networks take for granted.

Industrial devices face specific vulnerabilities when it comes to MAC spoofing that go beyond typical IT concerns. Many PLCs, VFDs, and HMIs run embedded operating systems with limited security features. They don't have sophisticated intrusion detection capabilities, and they often can't distinguish between legitimate traffic from an authorized engineering workstation and spoofed traffic from an attacker's laptop. If your network security relies primarily on the assumption that MAC addresses uniquely identify trusted devices, you're operating under a false sense of security. An attacker who gains physical access to your plant floor or connects remotely through a compromised VPN could spoof the MAC address of an authorized engineering laptop and potentially send commands to controllers, modify drive parameters, or extract sensitive process data.

Real world examples of MAC spoofing attacks in industrial environments tend to be underreported because facilities often don't have the visibility to detect them, and when they do occur, companies are reluctant to publicize security incidents. However, security researchers have demonstrated how MAC spoofing can be used to bypass poorly implemented access controls in industrial settings. In scenarios where a facility uses MAC address whitelisting to control which devices can connect to critical network segments, an attacker only needs to observe legitimate MAC addresses through passive network monitoring, then spoof one of those addresses to gain access. The attack becomes even simpler if the facility has documented their MAC addresses in network diagrams or asset management systems that aren't properly secured.

The situation becomes more complex in environments where wireless access points are used for HMI connectivity or mobile devices used by maintenance personnel. Wireless networks are particularly susceptible to MAC spoofing because an attacker doesn't need physical access to the network infrastructure. They can monitor wireless traffic from outside the facility, identify MAC addresses of authorized devices, and then attempt to connect using those spoofed addresses. This is one reason why modern OT security frameworks strongly recommend against using MAC filtering as a primary security control for wireless networks in industrial environments.

MAC filtering, the practice of configuring switches or access points to only allow connections from devices with specific MAC addresses, has been a common security measure in industrial networks for years. The appeal is obvious: it's relatively simple to implement, it provides a clear whitelist of authorized devices, and it adds a layer of protection beyond having no access control at all. Unfortunately, MAC filtering alone provides only the illusion of security. Because MAC addresses can be spoofed so easily, treating them as a reliable authentication mechanism is fundamentally flawed. An effective OT security strategy must treat MAC addresses as identifiers for network management and troubleshooting, not as credentials for access control.

The more robust alternative that's gaining adoption in industrial environments is 802.1X authentication, also known as port based network access control. Under 802.1X, devices must authenticate themselves using cryptographic credentials before they're granted access to the network. This authentication happens through a backend server, typically using the RADIUS protocol, and it relies on certificates or other credentials that are much harder to spoof than MAC addresses. When a device connects to a switch port configured for 802.1X, the switch doesn't simply check the MAC address against a list; it requires the device to prove its identity through a challenge response process that verifies possession of a valid certificate or other credential.

Implementing 802.1X in OT environments comes with practical challenges that need to be acknowledged. Many legacy industrial devices don't support 802.1X authentication because they were designed before this standard became common. A CompactLogix PLC from ten years ago simply doesn't have the capability to participate in an 802.1X exchange. This creates a migration challenge where facilities need to either upgrade devices, use authentication proxies that can broker 802.1X on behalf of devices that don't support it, or maintain hybrid security models where critical segments use 802.1X while legacy segments continue with less robust controls. The investment in managed switches that support 802.1X, the backend RADIUS infrastructure, and the certificate management systems represents a significant cost, but it's becoming increasingly necessary as OT networks face more sophisticated threats.

Network segmentation represents another critical layer of defense that moves beyond relying on MAC addresses for security. By dividing your industrial network into isolated segments using VLANs and carefully controlled routing between segments, you limit the impact of a compromised device or a successful spoofing attack. Even if an attacker spoofs a MAC address and gains access to one network segment, proper segmentation prevents them from pivoting to other critical areas. In a well segmented architecture, your HMI network might be isolated from your controller network, which is isolated from your enterprise network, with firewalls and access control lists governing what traffic can pass between segments. This approach aligns with Zero Trust security models that are increasingly being adopted in OT environments, where the fundamental principle is to never trust, always verify, regardless of where a connection request originates.

Zero Trust frameworks specifically address the limitations of perimeter based security and MAC address filtering by requiring continuous verification of every access request. Instead of assuming that a device with a known MAC address inside your network perimeter is trustworthy, Zero Trust models verify device identity, check security posture, and enforce least privilege access for every connection. This might mean that an engineering laptop needs to authenticate not just when it first connects to the network, but every time it attempts to communicate with a specific PLC or access a particular network resource. The implementation complexity is higher, but the security benefits are substantial, particularly in environments where the consequences of unauthorized access could include safety incidents or production shutdowns.

Certificate based authentication provides a foundation for these more sophisticated security models. Rather than treating MAC addresses as proof of identity, devices present cryptographic certificates that are much harder to forge or steal. Managed switches and firewalls can verify these certificates and make access control decisions based on certificate validity, expiration dates, and the specific permissions encoded in the certificate. For organizations working through broader digital transformation initiatives that include OT security improvements, understanding how manufacturing plant audits and digital transformation can identify security gaps and prioritize remediation efforts becomes essential. These assessments often reveal where legacy reliance on MAC filtering creates unacceptable risk and where investment in modern authentication mechanisms will have the greatest impact.

Even with strong authentication mechanisms in place, monitoring for MAC address anomalies remains an important defensive layer. The goal shifts from trying to use MAC addresses to prevent unauthorized access to using them as indicators of potential security incidents or configuration problems. Duplicate MAC addresses on a network, for instance, should never occur under normal circumstances. When a switch suddenly sees the same MAC address appearing on two different ports, it's either a sign of a spoofing attack, a misconfigured device, or a hardware failure. Having the tools and processes to detect these situations quickly is critical.

Many managed industrial switches include features for MAC address table monitoring that can alert you to suspicious activity. These switches maintain tables that map MAC addresses to specific physical ports, and they can be configured to send alerts or take defensive actions when anomalies occur. For example, you might configure a switch to disable a port if it detects a MAC address that shouldn't be on that particular port, or to send an SNMP trap to a monitoring system when a new, previously unknown MAC address appears on the network. The challenge in OT environments is tuning these alerts so they catch genuine security issues without generating false positives every time a technician connects a laptop for legitimate maintenance work.

ARP table monitoring provides another detection mechanism that can identify MAC spoofing attempts. The Address Resolution Protocol maps IP addresses to MAC addresses, and every device on a network maintains an ARP table with these mappings. When an attacker spoofs a MAC address, they often create inconsistencies in ARP tables across the network. Monitoring tools can detect when the same IP address suddenly resolves to a different MAC address, or when multiple devices report conflicting ARP information. This type of monitoring requires more sophisticated network visibility than simply checking switch MAC tables, but it can detect spoofing attacks that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Port security features on managed switches add another layer of defense by limiting which MAC addresses can connect to specific switch ports. You can configure a switch port to only accept connections from one or more specific MAC addresses, and to disable the port or send an alert if a different MAC address attempts to connect. This is more granular than network wide MAC filtering because it ties access control to specific physical locations in your network infrastructure. A port in the maintenance office might be configured to accept any MAC address because it's used by different laptops throughout the week, while a port that's hard wired to a specific PLC should only ever see that PLC's MAC address. If something else appears on that port, you want to know immediately.

Integration with Security Information and Event Management systems represents the most comprehensive approach to MAC address monitoring in industrial environments. SIEM platforms collect logs and alerts from switches, firewalls, and other network devices, then correlate this information to identify patterns that might indicate security incidents. A SIEM might notice that a MAC address that normally appears on the production floor suddenly showed up on a port in the office area, or that multiple MAC address changes happened in a short time window across different parts of the network. These patterns might be invisible when you're looking at individual switch logs, but they become obvious when viewed holistically through a SIEM.

The practical implementation of these monitoring strategies requires balancing security visibility with operational realities. OT networks often have limited bandwidth for management traffic, and some legacy devices don't handle frequent polling gracefully. You need to design monitoring systems that provide adequate visibility without impacting production system performance. This might mean using sampling rather than continuous monitoring in some network segments, or carefully scheduling when configuration audits run to avoid peak production times. The investment in managed switches, network monitoring tools, and SIEM platforms needs to be justified not just on security grounds but on operational efficiency, showing how better network visibility helps with troubleshooting and maintenance planning in addition to security incident detection.

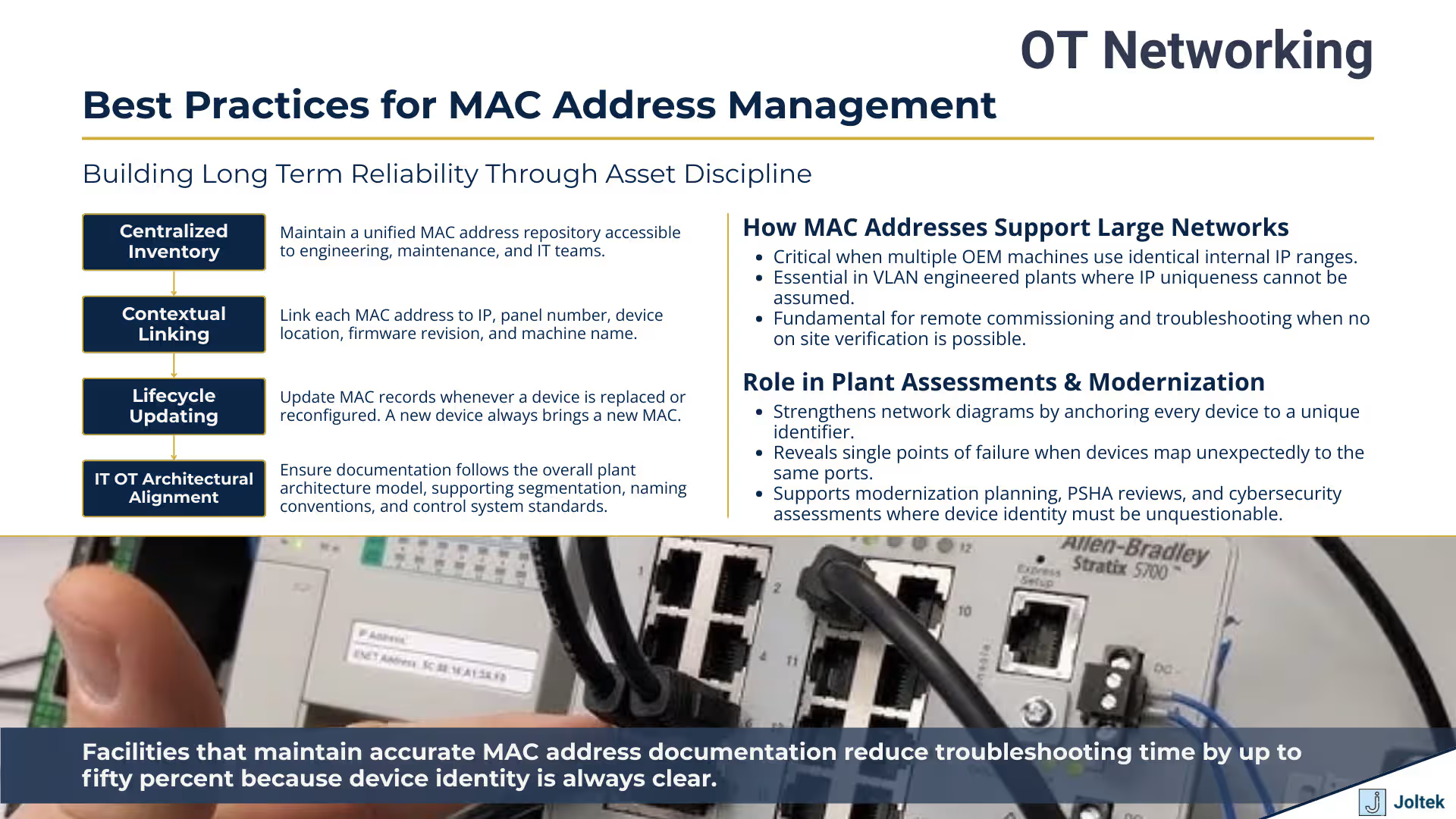

The single most important practice for managing MAC addresses across a complex industrial facility is maintaining accurate, up to date documentation. This sounds obvious, but the reality is that most facilities struggle with this fundamental requirement. Documentation tends to start strong during initial commissioning when engineers are carefully recording every device's MAC address, IP address, and physical location. Six months later, after a few emergency repairs, some equipment upgrades, and multiple visits from different contractors, that documentation is often outdated and unreliable. The gap between what your documentation says and what's actually on your network is where most configuration mistakes and security incidents originate.

Creating a MAC address inventory begins with a systematic survey of your existing equipment. This means physically walking down production lines, opening control panels, and recording the MAC address from the label on every networked device. You're documenting not just the MAC address itself but also contextual information that makes that data useful: which cabinet the device is in, what machine or process it's associated with, its current IP address, what type of device it is, and ideally a photo showing the label and the device's physical installation. This level of detail transforms a simple list of MAC addresses into a genuine asset inventory that maintenance technicians and engineers can actually use when they need to verify device identity or plan network changes.

The format and location of this documentation matters almost as much as its accuracy. A spreadsheet stored on someone's laptop is better than nothing, but it's not accessible to the team when that person is on vacation or has left the company. Asset management software designed for industrial environments provides a more robust solution by centralizing device information in a database that multiple people can access and update. These systems let you search for devices by MAC address, IP address, location, or device type. When you're standing in front of a switch wondering which of eight similar looking MAC addresses corresponds to the VFD you need to configure, being able to pull up that information on your phone or laptop immediately is the difference between confident, safe work and guessing with expensive equipment.

Modern asset management platforms can also track the history of each device. When a VFD fails and gets replaced, you don't just update the MAC address in the database; you record when the replacement happened, what the old MAC address was, and ideally why the replacement was necessary. This historical tracking becomes invaluable during troubleshooting. If you're investigating why a particular machine has been having intermittent communication issues, knowing that its VFD was replaced three months ago might point you toward a cabling problem introduced during that replacement, or a configuration setting that didn't get properly transferred to the new device.

Network diagrams serve as the visual complement to your tabular asset data. A well maintained network diagram shows not just the logical connections between devices but also includes MAC addresses and IP addresses for key equipment. These diagrams are particularly valuable during incident response when you need to quickly understand which devices might be affected by a network problem, or during planning when you're determining where new equipment will connect. The challenge with network diagrams is keeping them current as the network evolves. Many facilities resort to having both an official diagram that gets updated during formal change management processes and working diagrams that engineers mark up during day to day operations, with periodic reconciliation between the two. Neither approach is perfect, but the important principle is that diagrams should reflect reality rather than serving as aspirational documentation of how you wish the network looked.

Handling device replacements and RMA scenarios requires specific procedures around MAC address management. When you send a failed device back to the manufacturer and receive a replacement, that new device will have a different MAC address even though it's filling the same role in your network. Your documentation needs to reflect this change, but you also need to consider whether any other systems were tracking the old MAC address. If you're using MAC based port security on your switches, those configurations need updating. If you have monitoring tools that alert based on which MAC addresses should appear on specific network segments, those rules need adjustment. Some SCADA systems and historians identify devices partially by MAC address, and these systems might treat a replacement device as a completely new entity unless you properly migrate the configuration. Developing standard procedures for equipment replacement that include a checklist of everywhere MAC addresses might be referenced ensures that these updates don't get overlooked during the pressure of getting equipment back online quickly.

As industrial networks grow in complexity, understanding how MAC addresses function across VLANs and multiple network segments becomes essential. A common misconception is that MAC addresses only matter within a single physical network or broadcast domain. While it's true that MAC addresses primarily operate at layer two, and that routers generally don't forward MAC address information between different IP subnets, the practical reality in modern OT networks is more nuanced. You might have multiple VLANs configured on a single physical switch, with devices on different VLANs needing to communicate through routing, and understanding which MAC address corresponds to which device becomes critical for troubleshooting connectivity issues or security incidents.

VLANs allow you to logically segment your network even when devices share physical infrastructure. You might have production controllers on VLAN 10, HMIs on VLAN 20, and enterprise connectivity on VLAN 30, all running through the same managed switches. Each VLAN functions as its own broadcast domain, meaning that devices on VLAN 10 don't see broadcast traffic from devices on VLAN 20 unless you've specifically configured routing or trunking between them. From a MAC address perspective, this segmentation means that a switch maintains separate MAC address tables for each VLAN. The same physical switch port might see different MAC addresses depending on which VLAN that traffic is tagged with, particularly on trunk ports that carry traffic for multiple VLANs.

The complexity increases when you consider scenarios where multiple production lines or machines use identical IP addressing schemes but are isolated by VLANs. This is actually a common pattern in manufacturing facilities where each machine comes from an OEM with its own internal network using a standard address range like 192.168.1.x. You might have ten identical machines, each with a PLC at 192.168.1.10, but they're on different VLANs so there's no actual address conflict. When you're trying to connect to one of these PLCs for maintenance, knowing the IP address alone isn't sufficient. You need to know which VLAN that specific machine uses, and ideally you've documented the MAC address of each PLC so you can verify you're connected to the right one. This scenario where IP addresses aren't unique across your facility but MAC addresses still are demonstrates why MAC address documentation remains relevant even in complex, segmented network architectures.

Server connections at the plant level introduce another layer of consideration. Your SCADA server, historians, and application servers typically connect to multiple network segments to collect data from different areas of the facility. These servers often have multiple network interfaces, each with its own MAC address, and each interface might connect to a different VLAN or physical network segment. Documenting which server interface and MAC address connects to which production network is essential for troubleshooting. When you're investigating why a particular production line isn't reporting data to your historian, knowing which server network interface should be handling that traffic helps you quickly narrow down whether the problem is with the server, the network path, or the field devices themselves.

The convergence of IT and OT networks creates situations where traditional IT practices around MAC address management collide with OT operational requirements. IT departments are accustomed to dynamic addressing through DHCP, where devices might get different IP addresses each time they connect, and where MAC addresses are primarily used for initial network access control and then largely ignored. OT environments typically use static addressing where every device has a permanent, documented IP address, and where MAC addresses serve as the ultimate identifier when IP addressing becomes ambiguous or when you're dealing with device replacement scenarios. As facilities work toward more integrated IT/OT architectures, often as part of broader IT OT architecture and integration initiatives, establishing shared practices around network documentation that satisfy both IT security requirements and OT operational needs becomes a critical success factor.

Remote access to industrial networks has become increasingly common, driven by needs ranging from vendor support to centralized engineering teams supporting multiple facilities. This trend accelerated dramatically during recent years when travel restrictions made on site commissioning and troubleshooting impractical. However, remote access introduces specific challenges around MAC address verification that need careful consideration. When you're physically standing in front of equipment, you can read the MAC address label, visually confirm you're connected to the right device, and immediately see the results of any configuration changes. Working remotely, you lose all of that direct verification, which increases the risk of connecting to the wrong device or making changes that affect equipment you didn't intend to modify.

The fundamental challenge with remote access is that you're typically connecting through multiple layers of network infrastructure before reaching the device you want to configure. You might VPN into the facility network, then connect through one or more switches or routers, before finally establishing communication with a PLC or VFD. At each layer, you're relying on network addressing and routing to reach the correct device, but you don't have the physical confirmation that comes from tracing a cable from your laptop directly to the target equipment. This is where MAC address verification becomes your safety net. Before making any configuration changes to a device over a remote connection, verifying that the MAC address shown in your configuration software matches the documented MAC address for that specific piece of equipment is a critical safety check.

Best practices for remote device identification start with having accurate, accessible documentation that you can reference while working remotely. This means your MAC address inventory needs to be available through a web portal, shared drive, or asset management system that you can access from wherever you're working. Some organizations maintain spreadsheets with MAC addresses, but more sophisticated approaches involve asset management databases with search functionality that let you quickly look up devices by location, function, or network address. The key is that this documentation needs to be as current as possible. If you're relying on a network diagram that's six months out of date to verify MAC addresses remotely, you're potentially operating on incorrect information.

Network discovery tools provide another mechanism for remote device identification, but they need to be used carefully on live production systems. Tools like RSLinx from Rockwell Automation, TIA Portal from Siemens, or vendor neutral utilities can scan network segments and report back which devices they find, including MAC addresses, IP addresses, and often device types. The caution with these tools is that network scanning generates traffic that can impact devices with limited processing power or tight communication timing requirements. Running an aggressive network scan on a production line during operation might cause communication timeouts or unexpected behavior in controllers or drives. The safer approach is to either perform these scans during scheduled downtime, or to use passive monitoring tools that observe existing network traffic rather than actively probing devices.

Coordinating with on site personnel becomes essential when remote access alone isn't sufficient for confident device identification. Before making critical configuration changes remotely, having someone physically verify the device in question adds an extra layer of safety. This might mean asking a maintenance technician to read you the MAC address from the label while you confirm it matches what you're seeing in software, or having them physically trace network cables to confirm which device connects to which switch port. This coordination takes more time than working independently, but it's often necessary to maintain the same level of safety and verification that you'd have if you were on site. In facilities with robust change management processes, this kind of coordination might be formalized through work permits or remote access procedures that require local verification before specific types of changes can be executed.

The technology for remote verification continues to evolve. Some newer industrial devices include web interfaces that display the device's MAC address prominently on a status page, making remote verification easier. Asset management systems with integration to network monitoring tools can automatically verify that devices are still present at their documented MAC addresses and alert you to discrepancies. Despite these technological improvements, the fundamental principle remains: when working remotely, you need to be even more methodical about device verification than you would be on site, because the consequences of a mistake are just as severe but the immediate feedback that would tell you something went wrong might be delayed or filtered through multiple communication layers.

The journey through MAC address fundamentals, commissioning practices, and OT security reveals a simple truth that every engineer eventually learns the hard way. The MAC address is far more than a technical detail; it is your primary safeguard against configuration mistakes and a foundational element of network reliability. When you are working in front of a cabinet during commissioning or connecting remotely to a critical controller, there is no faster or more dependable way to verify device identity. IP addresses can be reused, mislabeled, or misconfigured. Panels can be crowded with equipment that looks identical. But the MAC address remains the unique anchor that lets you confirm with confidence that you are modifying the correct device. Building habits around verifying MAC addresses before every change is one of the most important steps toward reducing downtime and preventing costly errors on the plant floor.

The same principle applies to security and long term maintainability. As OT networks become more complex and more visible to the broader organization, the MAC address becomes a key data point in asset management, device replacement workflows, and segmentation initiatives. Facilities that struggle with undocumented systems or recurring network issues almost always discover that the root cause is a lack of reliable device identification. Standardizing how MAC addresses are captured, stored, and referenced removes ambiguity for both engineering and IT teams. It also provides the foundation for broader modernization work such as network segmentation, authentication upgrades, and enterprise level data initiatives. Organizations that adopt structured documentation practices, often through methods like a Plant Systems Health Assessment, consistently gain clearer visibility into their architecture and reduce the operational risk that comes from unknown or poorly tracked assets.

Ultimately, the value of MAC address discipline shows up not only in reduced engineering errors but also in stronger alignment across the technical functions of the plant. When teams maintain accurate inventories, diagrams, and standardized commissioning procedures, troubleshooting becomes faster, remote work becomes safer, and modernization efforts become more predictable. This alignment is a core requirement for IT OT integration projects where reliable device identity is essential for establishing secure connectivity and designing scalable architectures. As with any technical practice in manufacturing, consistency is what makes the difference. Maintaining MAC address documentation, verifying identity during configuration, and updating records during every replacement or migration builds a resilient operational baseline that supports both day to day reliability and long term strategic improvements.

If you have encountered MAC address mismatches in the field, struggled with undocumented devices, or are looking to build more reliable commissioning workflows, I invite you to share your experiences in the comments. Every plant and every system brings unique challenges, and the lessons learned across the community help strengthen the entire industry. If you are dealing with a specific scenario or want guidance on how to structure MAC address documentation within your organization, feel free to reach out with questions.