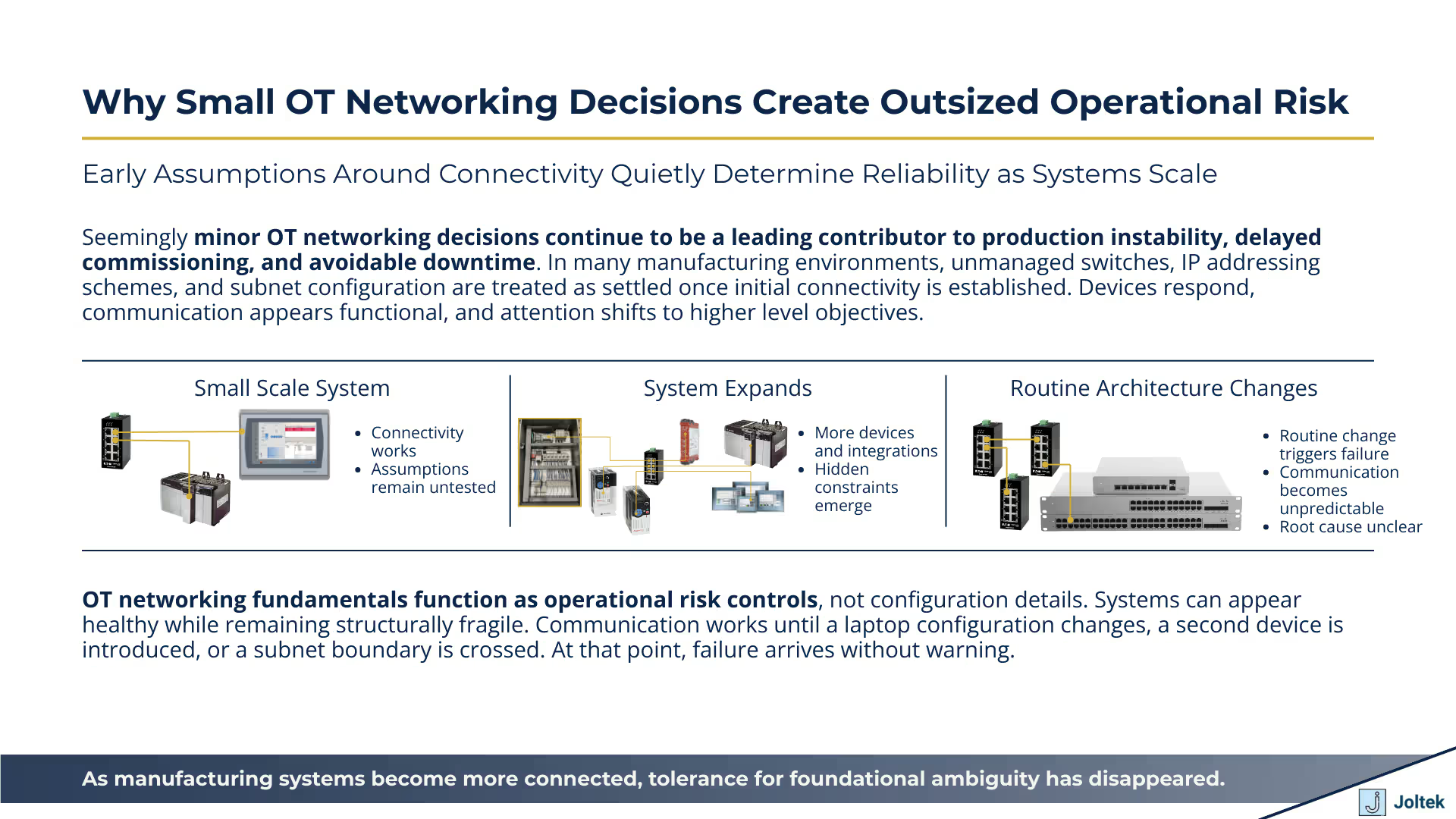

Seemingly minor OT networking decisions continue to be a leading contributor to production instability, delayed commissioning, and avoidable downtime. In many manufacturing environments, components such as unmanaged switches, IP addressing schemes, and subnet configuration are treated as settled details once initial connectivity is established. Devices respond, communication appears functional, and attention shifts to higher level system objectives.

This assumption does not hold over time. As production systems expand, integrate additional equipment, or connect to supervisory and enterprise platforms, these early decisions begin to constrain reliability. Networks that functioned adequately at small scale often fail to behave predictably under normal operating conditions. The resulting issues are rarely catastrophic at first. They surface as intermittent communication loss, unexplained device unavailability, or fragile behavior during routine changes.

OT networking fundamentals should be viewed as operational risk controls rather than technical configuration details. The transcript underlying this article demonstrates how systems can appear healthy while remaining structurally fragile. Communication works until it does not. A laptop configuration changes, a second device is introduced, or a subnet boundary is crossed, and previously stable systems fail without clear indication of why.

From a leadership perspective, these failures are problematic not because they are complex, but because they are difficult to anticipate and diagnose. Responsibility becomes fragmented across engineering, maintenance, and IT teams. Recovery time increases, and confidence in the underlying system erodes.

As manufacturing organizations pursue greater connectivity, the tolerance for foundational network ambiguity has effectively disappeared. Data driven operations, remote access, centralized monitoring, and cross site standardization all depend on consistent behavior at the control network level. When that foundation is built on undocumented assumptions or convenience driven decisions, modernization efforts slow, risk increases, and change becomes progressively harder to justify.

This article examines unmanaged switches, IP addressing, and subnet configuration through the lens of operational reliability. The objective is not to revisit networking theory, but to clarify why these fundamentals continue to determine whether production systems remain stable as complexity increases.

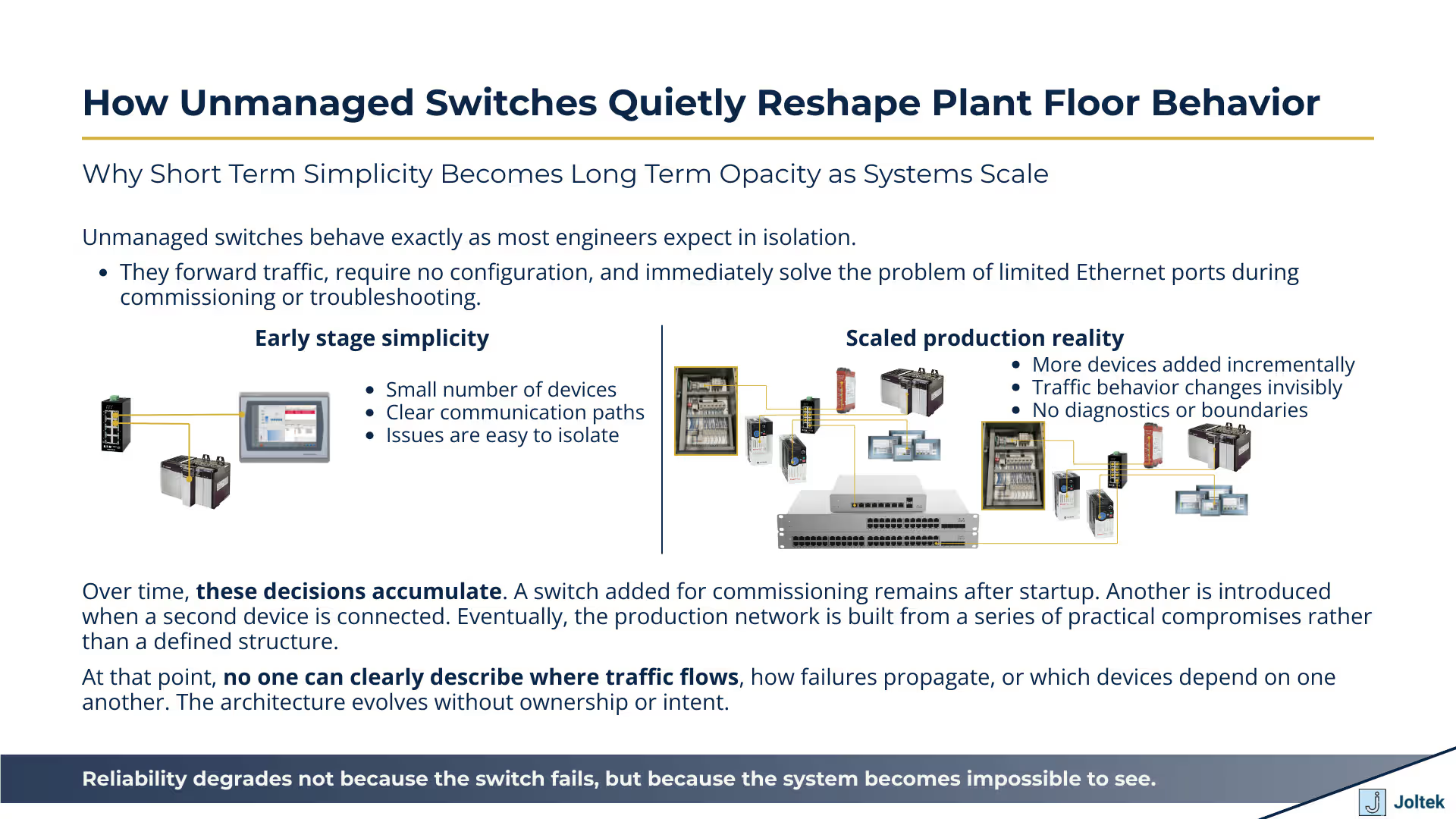

Unmanaged switches remove visibility and control at the exact moment systems begin to grow. In isolation, an unmanaged switch behaves exactly as most engineers expect. It forwards traffic, requires no configuration, and immediately solves the problem of limited Ethernet ports during commissioning or troubleshooting. In early stages, this simplicity feels efficient and appropriate. The transcript reflects how quickly unmanaged switches become the default solution when a laptop, a drive, and a controller all need to communicate at the same time.

The problem emerges when this temporary convenience becomes embedded in the production environment. Once unmanaged switches are left in place and additional devices are connected, the network begins to change in ways that are not observable. Traffic increases, broadcast behavior expands, and devices that were previously quiet now compete for attention. Because unmanaged switches offer no diagnostics, no traffic insight, and no indication of load, engineers lose the ability to understand what is happening on the wire. When communication degrades, teams are forced to guess whether the issue sits with a device, a cable, or the network itself. Reliability suffers not because the switch fails, but because the system becomes impossible to see.

Physical port limitations often dictate network design more than intentional architecture. On the plant floor, decisions are frequently shaped by what is immediately available. A laptop has one Ethernet port. A drive has a single network connection. A controller exposes two ports, but only one is configured. In that moment, adding an unmanaged switch is the fastest way to move forward. The transcript illustrates this exact scenario, where the switch exists not as a design choice but as a necessity to continue work.

Over time, these decisions accumulate. A switch added for commissioning remains after startup. Another is added when a second device is introduced. Eventually, the production network is built from a series of practical compromises rather than a defined structure. At that point, no one can clearly describe where traffic flows, how failures propagate, or which devices depend on one another. What began as a short term workaround becomes permanent infrastructure, and the network evolves without ownership or intent.

This is why many plants struggle to explain their network topology or identify failure domains when issues arise. The architecture was never consciously designed. It was assembled incrementally, driven by port availability and time pressure rather than long term reliability considerations.

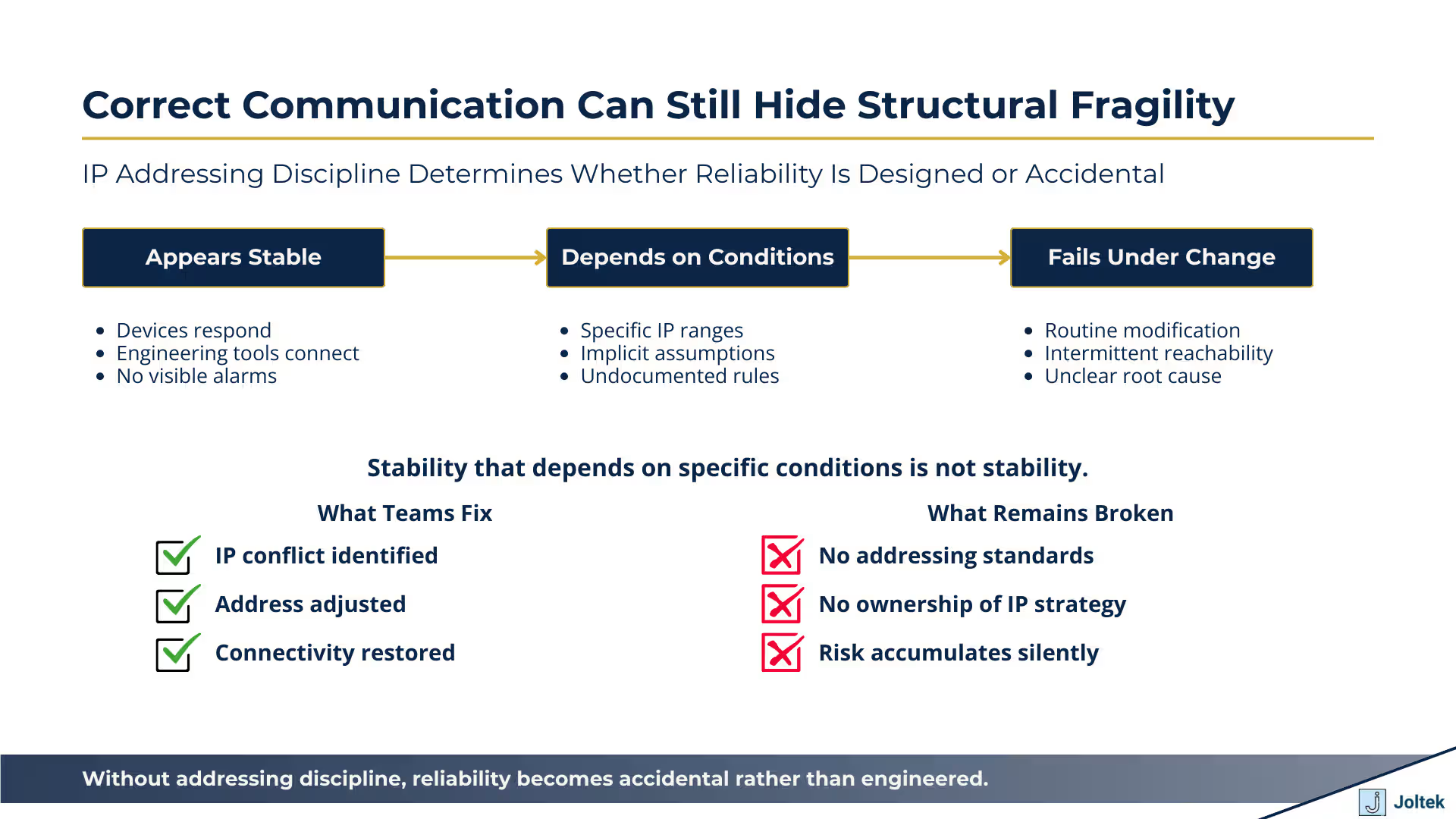

Devices can respond correctly while the system remains structurally misconfigured. One of the most misleading aspects of IP based communication in OT environments is how easily a system can appear healthy. A device responds to a ping. A configuration tool connects without error. From the outside, everything looks correct. The transcript highlights how this apparent success depends on very specific conditions that are often accidental rather than intentional.

During commissioning, engineers confirm connectivity and move forward, assuming the addressing scheme is sound. In reality, the system may only be functioning because all devices happen to sit within a narrow and fragile configuration window. A single change to a laptop address, the addition of another device, or a modification to a subnet parameter can break communication entirely. When this happens, failures do not follow a clean pattern. Devices may drop in and out of reach, or respond in some tools but not others. For leadership teams, this is a particularly dangerous situation because it creates instability without obvious indicators of where the problem resides.

Address conflicts are symptoms. Inconsistent standards are the root cause. When IP issues surface, they are often described as isolated conflicts that require quick resolution. An address is changed, communication is restored, and the incident is considered closed. The transcript makes clear that this approach treats the symptom rather than the system. Without a consistent addressing strategy and clear documentation, every change introduces new assumptions that remain untested until the next failure occurs.

Over time, these incremental fixes create an environment where only a small number of individuals understand which address ranges are safe, which devices are sensitive to change, and which combinations should be avoided. This reliance on tribal knowledge increases operational risk and slows response during critical events. From an executive standpoint, the concern is not the presence of IP conflicts themselves, but the absence of shared rules governing how addresses are assigned and maintained. Without that discipline, reliability becomes dependent on memory rather than design.

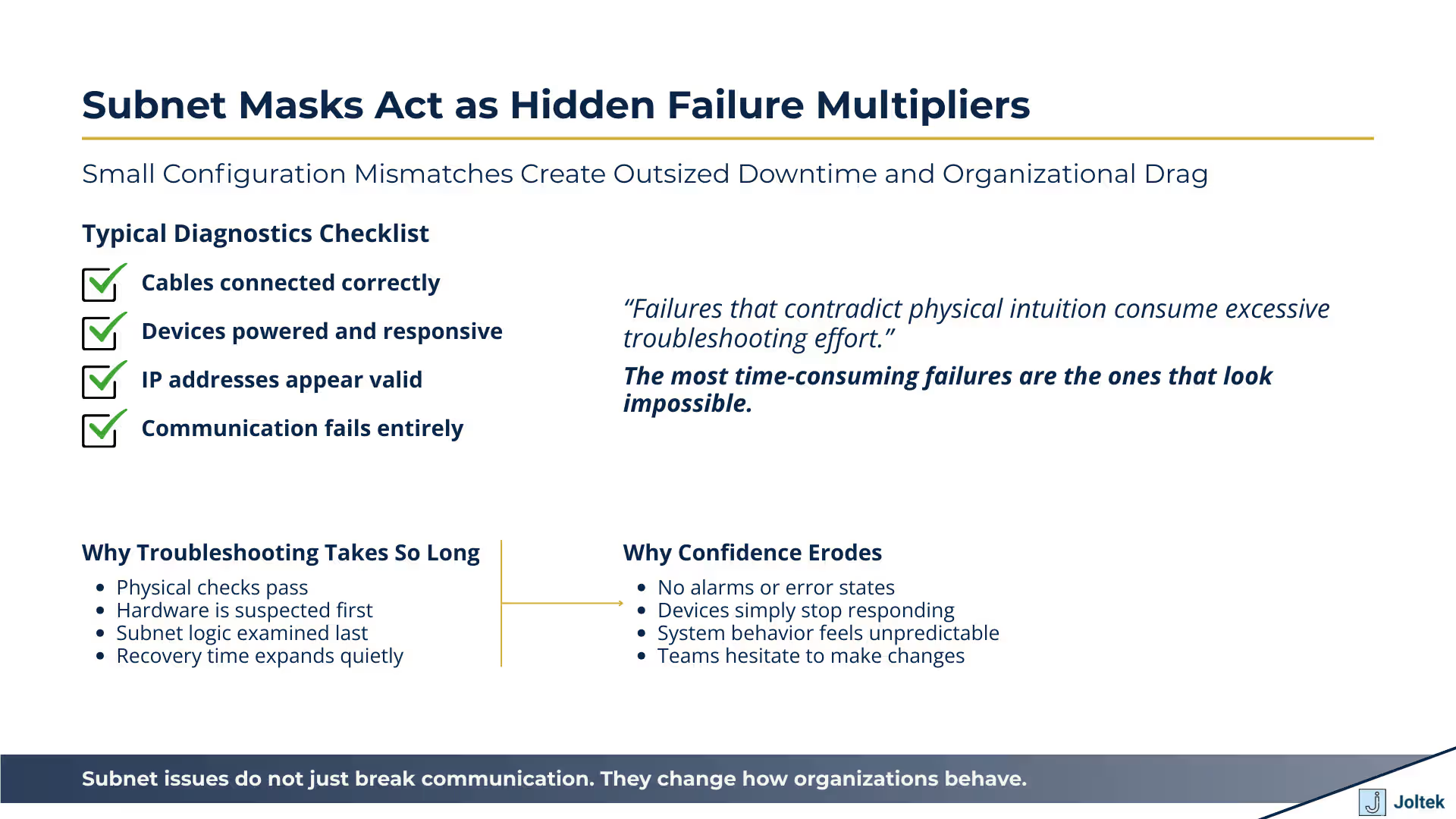

Subnet configuration errors produce failures that look random but are entirely deterministic. Subnet masks sit in an uncomfortable middle ground between physical infrastructure and application behavior. When they are misaligned, nothing about the failure feels intuitive. Cables are connected correctly. Devices are powered and healthy. IP addresses appear to be in the expected range. Yet communication fails completely. The transcript shows this clearly. A device that was reachable moments earlier becomes unreachable after a seemingly minor change, even though nothing physical has changed.

From an operational standpoint, this type of failure is especially damaging because it defies first level troubleshooting instincts. Teams naturally suspect cabling, ports, or hardware faults. Time is spent reseating connectors, swapping devices, or rebooting systems. Only later does the investigation move toward addressing and subnet logic. For executives, the key point is not the technical detail of subnet masks, but the impact on recovery time. These issues consume far more troubleshooting effort than their simplicity would suggest because they are invisible until someone looks in exactly the right place.

Subnet related issues undermine trust because they fail without warning and without clear indicators. Unlike component failures that present alarms or error states, subnet mismatches often provide no direct feedback. Devices simply stop responding. In complex environments, this creates doubt about the stability of the entire automation stack. Teams begin to question whether systems can be safely modified or expanded without unintended consequences.

This dynamic matters at a leadership level because it changes behavior. When teams lose confidence in the predictability of the network, they become more cautious about change. Improvements slow down. Modernization initiatives are delayed. What began as a basic configuration oversight becomes a cultural barrier to progress.

Subnet changes often require device specific knowledge that is not consistently retained. Applying subnet modifications is rarely as simple as changing a value in one place. The transcript highlights the need to adjust multiple parameters and reboot devices before changes take effect. Each vendor implements this process differently. Drives, controllers, and network modules all expose subnet configuration in their own way, often buried deep in menus or parameter lists.

When this knowledge lives only with individuals rather than in documentation, the organization becomes fragile. Routine changes take longer. Mistakes are more likely. Recovery from issues slows dramatically when the person who last touched the configuration is unavailable. Over time, this creates extended downtime from problems that should be straightforward to resolve. The risk is not the complexity of the technology itself, but the lack of shared understanding around how these fundamental settings behave across the installed base.

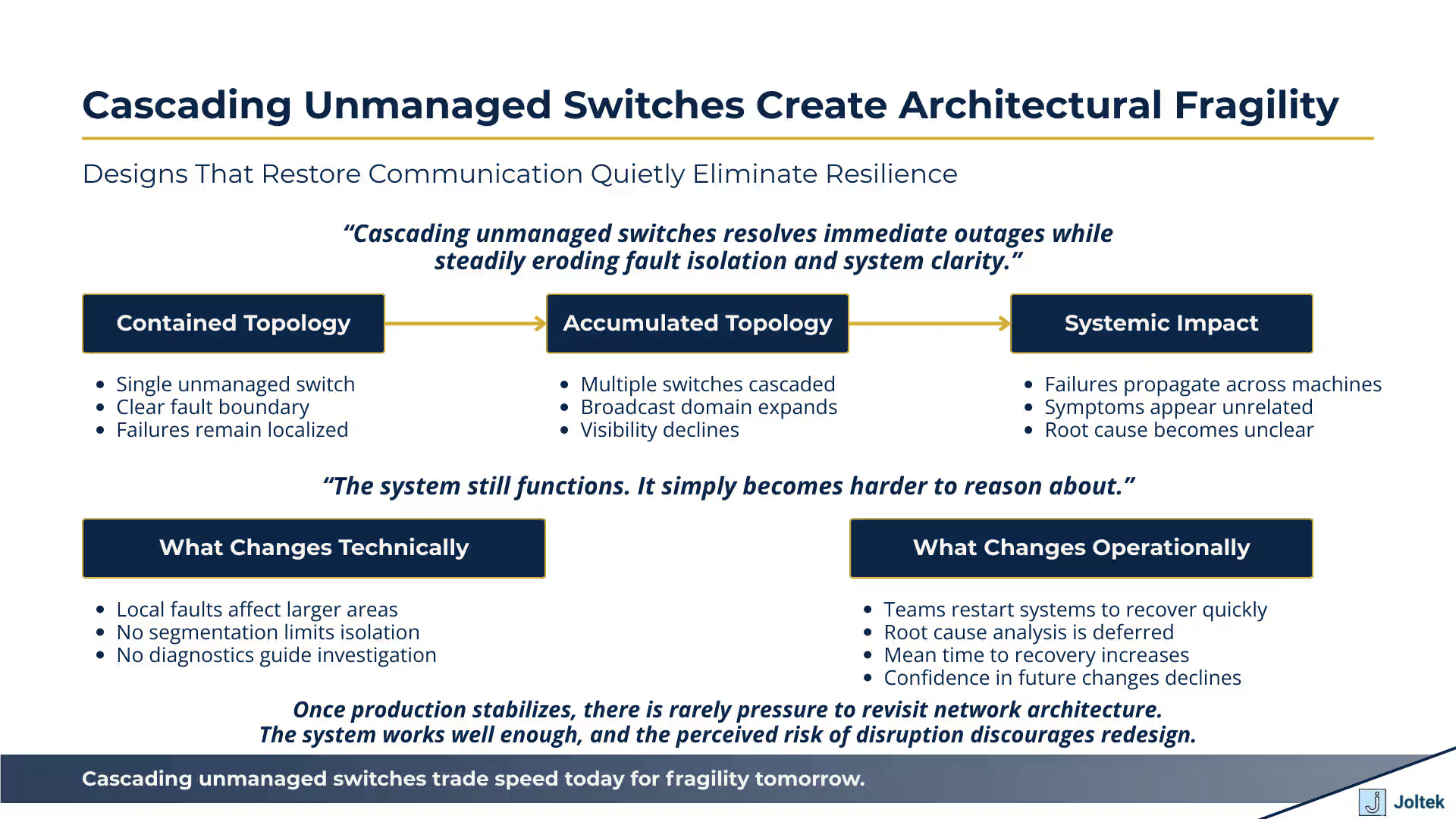

Extending unmanaged switches increases reach but collapses fault isolation. The transcript demonstrates a pattern that is extremely common on the plant floor. Communication fails when there is no physical path between devices, then immediately recovers once a second unmanaged switch is connected. From an engineering perspective, this reinforces the idea that the solution is valid. The system works again, production can continue, and attention moves elsewhere.

What is less visible is how each additional switch changes the behavior of the network. Every unmanaged switch expands the broadcast domain and removes another opportunity to understand where traffic is flowing. When a fault occurs, it no longer affects a single device or cable. It propagates across a wider portion of the system. Diagnosing the root cause becomes more difficult because there is no clear boundary between normal behavior and failure. The network still forwards traffic, but the system as a whole becomes harder to reason about.

From a business standpoint, this is a trade that favors speed over resilience. The architecture supports immediate needs but provides no margin as the system grows. When load increases, when devices age, or when new equipment is introduced, failures appear in places that seem unrelated to the original change.

Cascaded unmanaged switches amplify the impact of small changes. In a simple network, a misconfigured device or failing cable affects a limited area. In a cascaded design, the same issue can disrupt communication across multiple machines or an entire line. Because there is no segmentation or visibility, teams often respond by restarting systems or rolling back recent changes without understanding the underlying cause.

This dynamic increases mean time to recovery and creates hesitation around making improvements. Each change carries the fear of unintended consequences, even when the change itself is minor.

Lack of architectural ownership allows temporary solutions to become permanent. Once production stabilizes, there is rarely a forcing function to revisit network design. The system works well enough, and the risk of disruption discourages change. Over time, the original context of why switches were added is lost. Documentation lags behind reality, and the architecture becomes something the organization inherits rather than chooses.

It is only after a major outage that the cost of this approach becomes visible. At that point, redesigning the network requires downtime, coordination, and capital that could have been avoided with earlier intervention. The persistence of these designs is not a technical failure. It is an organizational one, rooted in the absence of clear ownership over how the control network should evolve as the plant grows.

Advanced platforms cannot compensate for weak network foundations. The transcript reinforces a reality that is easy to overlook when organizations focus on new tools, analytics platforms, or automation software. Most OT network failures do not originate from sophisticated cyber attacks or advanced software defects. They originate from unmanaged growth, inconsistent IP addressing, and subnet behavior that is poorly understood or undocumented. These issues persist because systems often appear functional until they are placed under pressure. When that pressure arrives, the failures are abrupt, disruptive, and difficult to explain.

As manufacturing systems become more connected, the consequences of these fundamentals grow. Connectivity increases dependency. Dependency reduces tolerance for ambiguity. A network that once supported a single controller and drive must now reliably carry supervisory traffic, diagnostics, and data flows beyond the machine. If the foundation is fragile, every additional connection increases risk rather than value.

Organizations that approach OT networking as strategic infrastructure create the conditions for confident modernization. This does not require excessive complexity or overengineering. It requires clarity. Clear addressing standards. Clear ownership of network design decisions. Clear understanding of how unmanaged components behave as systems scale. When these fundamentals are treated with the same discipline as safety systems or critical assets, teams gain confidence in their ability to change, expand, and improve.

Modernization succeeds when systems behave predictably under change. That predictability is not created by advanced technology alone. It is created by disciplined fundamentals that allow advanced technology to perform as intended.